Why Your Endurance Isn't Enough

A lot of people only want to put time into things that can deliver them quantifiable results, which is quite reasonable, really. When Kris and I spoke in the past about the “immeasurables” that influence climbing performance, (attributes that can't be measured - like confidence, tactics, or the ability to try hard), I had someone tell me that they didn’t believe in immeasurable qualities. As a numbers person, they believed that all things could be measured, even if we haven’t figured out how to measure them yet. Touché.

While that’s a great point, the “ill-defined-and-not-yet-reliably-measurables” doesn’t quite have the same ring to it. However, their point gave me a lot to think about these past few months.

As a response, today’s post is for all of you number people out there. So listen up, nerds.

The author about to discover just how measurable his slab skills are on the crux of "Lord Voldemort" (5.14a), New River Gorge, West Virginia.

Photo: Rachel Avallone

“The brain is the most important muscle for climbing.”

One of the main pillars of performance, and maybe the hardest (though not impossible) to measure, is the mental side of climbing. Let’s be honest, mental training isn’t cool to talk about. Few things make people zone out faster than talking about mindfulness.

We’ve all seen people who have incredible confidence while bouldering or sport climbing, and it’s clear how much of a role it plays in their ability to get things done under pressure. Even though we can see that there are tangible benefits, few of us ever put in the time to improve our mental game.

Someone once told me that the person who needs to work on their mental game isn’t the same person who needs to be doing physical training for climbing. They thought that needing to work on your head game meant that you're terrified of falling or so inexperienced that you are beneath doing "real training" for climbing. I’m here to argue otherwise.

While chatting with a friend who is a high-level swimmer turned rock climber, we got on the subject of prior sport experience. He argued that people who were competitive endurance athletes before becoming sport climbers have a huge leg up on people who didn’t share that same background. His reasoning was that competitive endurance athletes come into climbing having already experienced hours upon hours of dealing with discomfort while performing.

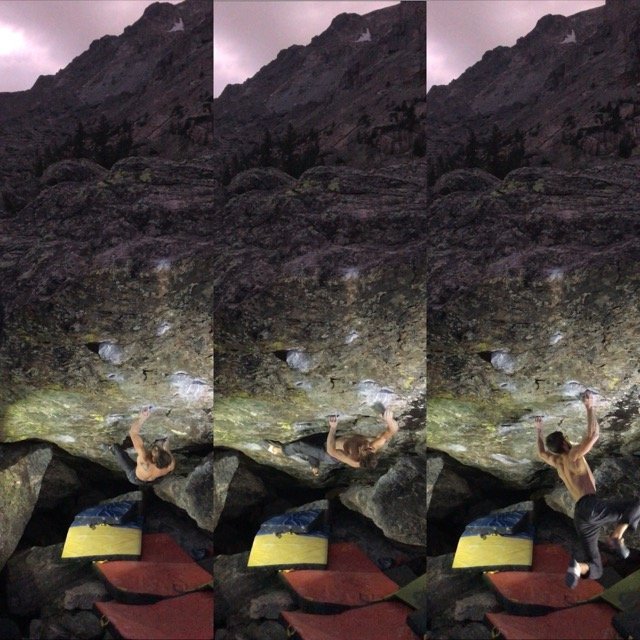

“It goes back to our conversation with Jerry Moffatt. It always comes down to one split second - it’s the moment right before you’re about to fall. What do you do in that moment? Do you let it wash over you and give up, or do you just keep going? That’s what’s so cool about climbing, and what keeps me coming back to it every day.”

That split second on "Skeletor" (5.13c), Rifle, Colorado. Photo: Rachel Avallone

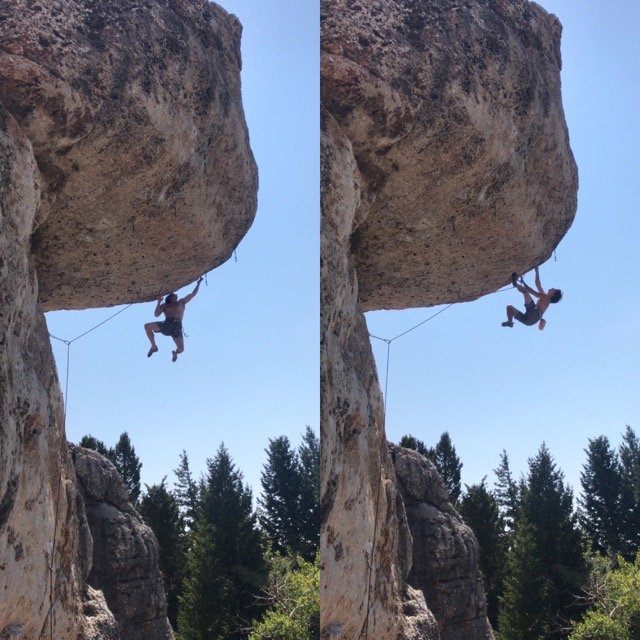

Climbing is a unique sport in that a single mistake can end an entire effort immediately. In almost every other sport, you can slow down and keep going or make up for mistakes later on. It’s because of this fact that sport climbers don’t get the opportunity to spend much time in the "red zone." If you get to the point where you are redlining on a sport climb, even the smallest mistake can spit you off. Or if you don't get to a rest quickly then you'll fall soon enough from the pump. There is also the fear component - both of falling and of failing - (are you climbing to send, or climbing not to fall?), that compounds this feeling of overwhelm while pumped and can make things spiral out of control in a matter of seconds.

Kris and I have previously discussed how we feel that a common mistake of today’s sport climber is that while they do a great job becoming fit, they often fail to spend enough time learning how to climb while severely pumped.

It doesn’t matter how fit you are...

...if you're going to try to push your limits on a rope, you will get uncomfortably pumped. And that’s something you need to learn how to deal with.

This brings us back to that earlier conversation where Kris and I referred to being able to fight and stay composed while pumped as one of those "immeasurables."

Earlier this spring, I came across the book "Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance" by Alex Hutchinson. In it, he discusses research on how the mind affects endurance and our physical limits. It felt like a more tangible discussion of what Kris and I have been trying to say, and I believe this is something really important that isn’t being discussed in climbing.

While this isn’t a how-to for hacking your brain into making you a super athlete, it is a great data-driven argument for why we should be giving some time to the mental side of our sport.

If this is something that interests you, a good starting place would be this episode of the Ready State Podcast (hosted by Kelly and Juliet Starrett of Mobility WOD) that features Alex Hutchinson.

If you enjoy the podcast, check out his book (linked above). It’s a page-turner that'll give you a lot to think on.

**I believe there are plenty of people who have done an excellent job discussing the "how" of mentally preparing for sports, and that extends beyond the scope of this post. My goal with this post is to show that there is more to mental training than taking practice falls, or all the baggage that comes with terms like "mindfulness." Hopefully, you'll find that these resources will provide you a good research-backed "why" in the argument for becoming a mentally stronger climber.**

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.