Sharpen Your Saw

Experienced climbers are incredible at lying to themselves. They’ll tell you they take a long-term approach to improvement, but their actions show them struggling to prioritize beyond the next few months. It’s not their fault though. Not entirely, at least. Trying hard and trying to perform are fun, and climbing’s lack of an in-season and off-season makes it feel like any time spent not chasing sends is a missed opportunity.

Someone will tell me that they want to “level up” this year. They are going to double down on training, take things seriously, play the long-game, put in the hours, and finally break through this plateau. But they also want to be climbing well on a trip in six weeks…

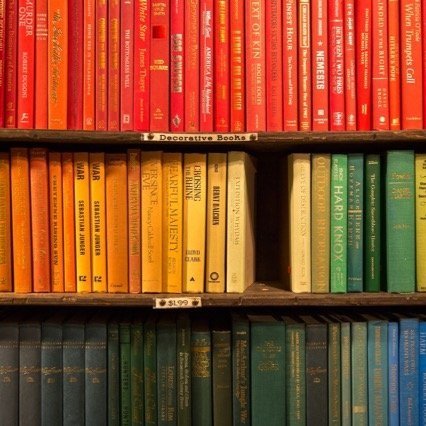

In Stephen Covey’s book 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Chapter 7, “Sharpen Your Saw”, opens with the following story:

Suppose you were to come upon someone in the woods working feverishly to saw down a tree.

“What are you doing?” you ask.

“Can’t you see?” comes the impatient reply. “I’m sawing down this tree.”

“You look exhausted!” you exclaim. “How long have you been at it?”

“Over five hours,” they return, “and I’m beat! This is hard work.”

“Well, why don’t you take a break for a few minutes and sharpen that saw?” you inquire. “I’m sure it would go a lot faster.”

“I don’t have time to sharpen the saw,” they say emphatically. “I’m too busy sawing!”

Experienced climbers will say that they want to level up, and then in the same breath tell you their plan to spend the entire year trying to climb as many objectives as possible. They want to be in good shape for multiple seasons and trips, and even their gym time has them chasing sends of hard board problems and party-trick strength exercises. They are so busy sawing away at performance that they don’t pause to realize they’ve become dull from years of endless effort.

I get it. Performing is fun. Sending new climbs is fun. For the first few years of climbing, this approach of always trying to be at the top of your game worked for you. There’s a lot to be learned from the process of projecting near your limit and pushing those boundaries. The benefits of learning how to perform and the tactics surrounding it offset the potential losses you might have from short-term thinking in those early years. Building strength, fitness, and skill all take time, though. The more time we spend each year trying to optimize for a specific trip or a performance period, the less time we have to develop those base components.

What if this lull you’re in right now isn’t because you are plateaued, reaching your genetic potential, or in need of more complex and specialized training, but instead because you’re keeping yourself in a constant loop of trying to perform? If you want to continue making progress year after year and to have longevity in this sport, take a step back. Sharpen your saw.

Despite being constantly present and often the reason we fail, Rhythm is the most underrated of the Atomic Elements of Climbing Movement.

Long-time friends Nate and Ravioli Biceps discuss lessons they’ve pulled from video gaming that can help inform our climbing.

There’s A LOT of great information out there on how to climb harder. But it’s tough to sort through…

Short climbers are good at getting scrunchy, and tall climbers are good at climbing extended, right? Wrong.

One of the most common places things start to fall apart is at the very beginning of the move.

We know spending time on a finishing link is smart tactics for hard climbs. So why not apply the same concept to individual moves?

Learning when and how to compensate for a weakness is a skill. And skills need to be practiced.

Lowball boulders, while not as proud, can still teach us new movement, new ways to utilize tension, and force us into finding new techniques.

I never thought I’d be recommending this, but some of y’all should be putting less effort into becoming technically better climbers.

Training principles are important, but when they creep into performance, your climbing will suffer. Nearly every time.

We have become collectors of dots. But there’s one major thing that happens when we connect dots that is entirely lost in mass dot collection: critical thinking.

Do you really have terrible willpower? Or are you surrounded by distractions and obstacles?

You have a climbing trip coming up. The rock is different. The style is different. Your pre-trip time is short and the number of days you’ll be climbing, even shorter…

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

Discussion around grades can be so polarizing that many of us avoid the topic.

Climbing starts off as this self-feeding cycle that has you wishing you could climb seven days a week. What happens when this cycle stops bringing improvement though?

Use strength to leverage every other aspect of your climbing, not replace them.

If everything you do is a finger workout, then when do your hands get a chance to recover?

There is a common theme between a grilled cheese sandwich and good training advice.

The more accurately we define our problems, the more approachable it will feel to find solutions.

Maybe the most understated way of getting better is to build fallback successes into your plan.

How much time should climbers spend becoming more well rounded vs. improving their strengths?

As cool as assessments and standards are, they can easily leave people settling for “good enough” when they have the potential to do much more.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.