It Doesn't Get Easier Than This

When I was five years into climbing, I hated the grade V4. I climbed outside as much as I could, and was starting to feel solid in the V7 range. For some reason, V4 seemed harder than it should be. V0-V3 was feeling good, and falling on V5 and V6 made sense because those were hard grades. I felt like I shouldn’t have to work so hard for V4, though. What was I missing? Clearly, I was doing something wrong.

I remember having a conversation about this with a friend who was a much more experienced climber than me. He had climbed several V13’s, and had flashed up to V12 at that point.

“How can V4 still feel hard if I’m now climbing V7?”

He said that no matter how much better and stronger he got, V10 never felt all that much easier than his first year of climbing that grade. He still had to try hard to do them. He had a new range of how hard he could try, and he had a higher success rate with them now than he did then, but they were still hard.

I didn’t want to believe that at the time.

Recently, I was talking with a client who was really hitting her stride with her winter bouldering season. She was climbing the best she ever had and sent me this message:

“My fingers feel stronger, my tension is good, the rock is sticky. Hard moves feel hard, but I don’t fall as much?? It’s crazy.”

In a Nugget patron episode with Jonathan Siegrist from November, 2020, he said:

“We all have an idea and a concept of how we feel we should perform or we ‘deserve’ to perform, and more often than not, that gets in our way as opposed to empowers us. It’s really imperative that we always respect how hard climbing is. Really hard climbing is always going to be hard.”

“13a was hard for me 15 years ago, and it’s still hard. I might do it easier now, but I never climb 13a or 12d and am like, ‘That was easy. I could do it blindfolded with vaseline all over my hands,’ like, no, it’s still really hard. It’s a different sensation, but it doesn’t just go away. Climbing is just hard. At least that’s my experience. I’m always surprised. It’s like ‘Damn, it just doesn’t get that much easier does it? It’s still hard.’”

It’s easy to look back at how challenging V0-V2 was for us early on in our climbing, compare that to how it feels now, and assume that the same pattern should continue up the grade scale. Unfortunately, as climbing becomes more advanced and the challenges we face require us to stretch ourselves mentally, physically, technically, and tactically, the perceived difficulty stops falling away so dramatically. Hard climbing will always feel hard.

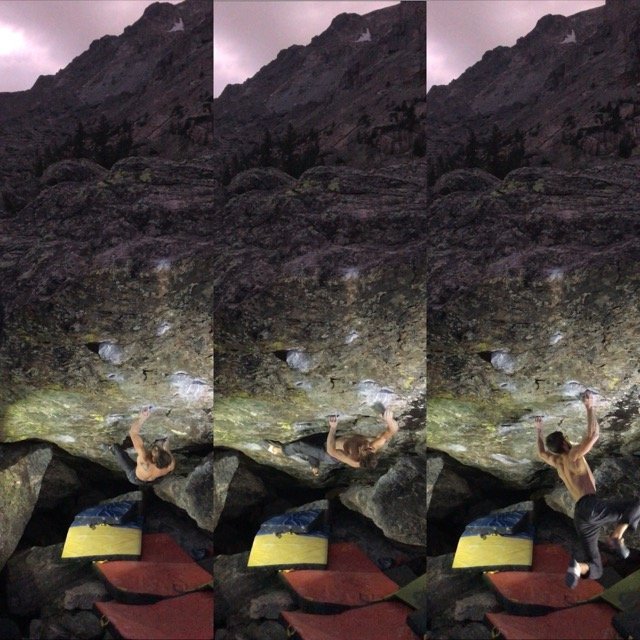

Smith Rock, where all climbing is hard climbing. Photo: Nina Caprez

There are a few takeaways from this that I think are important:

There’s value in looking at objective results while attempting a climb, rather than relying solely on how things feel. Look at your success rate. If moves on your project still feel hard, but you’re doing them more consistently and in bigger links, then you’ve improved regardless of how subjectively they feel. V5’s might still feel hard, but if you’re doing them faster and in a broader degree of styles than last year, then you’ve improved.

Hard climbing is hard. The more you can develop your mindset around that concept, the more mentally robust you will feel when you encounter climbs that challenge you. You’re trying it because it’s a challenge. Lean into it. With time, you might even learn to enjoy the challenge.

When you try a climb that is a few grades below your max and it feels unnecessarily hard, ask yourself, “Is this actually hard or am I just expecting it to be easy?” It might seem like semantics, but if you go into a moderately difficult challenge expecting it to feel easy, then it’s going to feel incredibly hard. When in doubt, try harder.

Stop trying to use training as a method to skirt around trying hard. It’s tempting to hit pause on the process to get more finger strength, explosive power, endurance, or a big enough grade pyramid that the climbs you want to do will stop feeling so hard. In your earlier years of climbing you can get away with this, but as you progress you’ll have to unlearn this pattern.

Eventually you’ll find yourself at the base of a climb that you can’t become overpowered for. Even if you have more than enough strength and fitness to do it, you’ll finally be forced to try hard and stretch your mental, technical, and tactical abilities to do so. You’ll feel unprepared from so many years of finding success by only out-training climbs. It’s not a fun wall to hit. Keep training to get stronger, fitter, and better, but use those things as a way to improve the quality of your effort rather than replace it.

Trying hard is hard. No matter how much enjoyment you get out of it, it’s still draining. Be kind to yourself. Don’t be afraid to take some time during the year to throttle back a bit and let yourself recharge. A few weeks of climbing a few grades easier where you aren’t trying quite as hard and the stakes don’t feel so high can go a long way to rebuild your drive for the challenge.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.