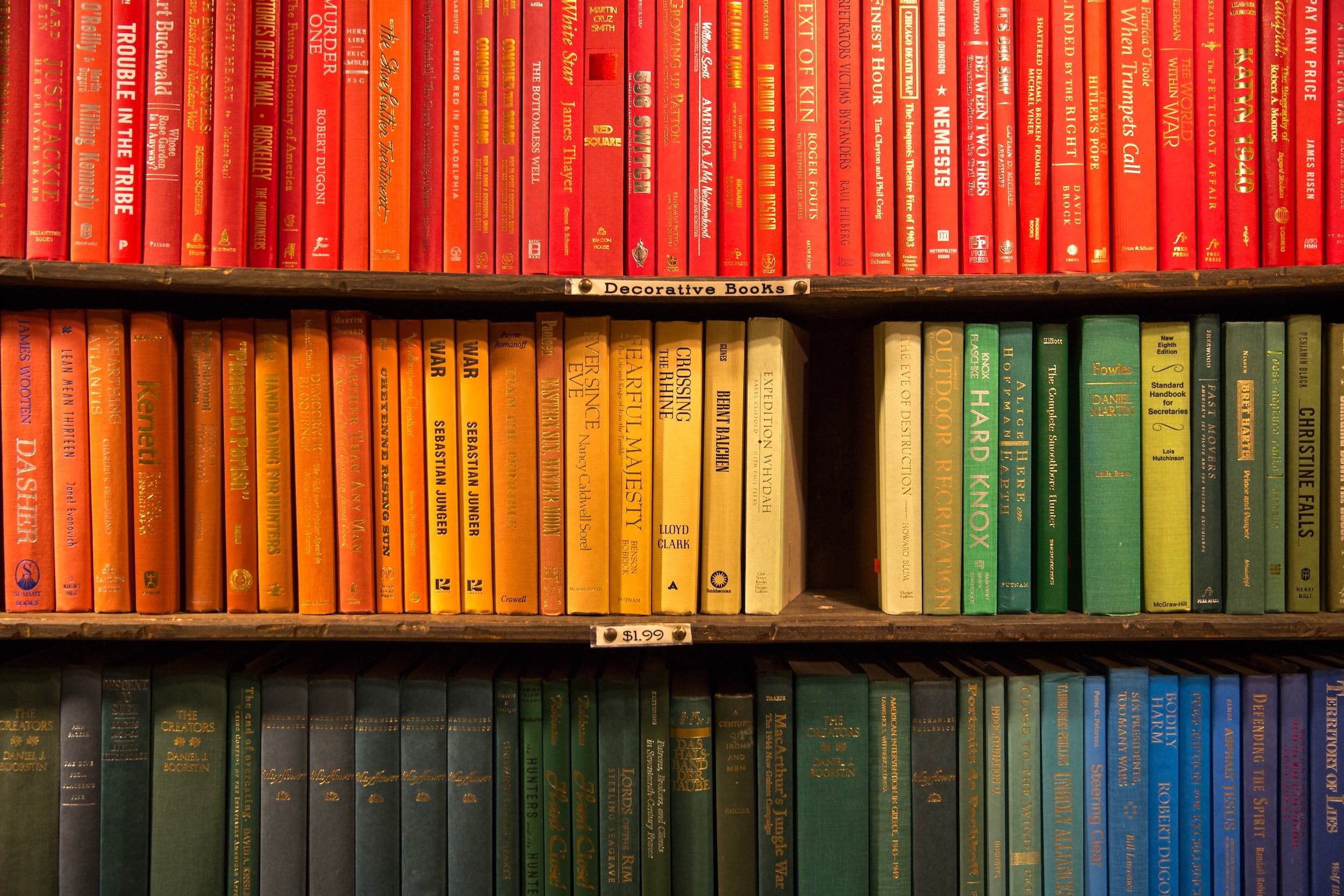

Lessons from the Library

Embracing something new in climbing can feel a lot like trying to read a book for the first time. There are times when you pick up a book that you should like, all your friends like it and it seems like something you will enjoy, but you can’t get into it. That same book, when given a second chance months or years later when you are in a different place in life or in a different headspace, might reveal itself to be an all-time favorite.

At some point in climbing, we all experience a moment of finally connecting with a lesson or concept after being presented with it countless times. This might be something that you’ve heard others discuss or something you’ve been directly told you should improve on. You might have been told so many times by friends or climbing partners to try this thing that you’ve gotten sick of hearing it. This could range from learning to use momentum, starting to train, having more confidence on harder grades, or leaning into climbs that challenge you regardless of their grade. Even though this idea isn’t new to you, it’s never been something you connected with until recently.

(Don’t worry, I’m not here to tell you to admit to your climbing partners that they’ve been right this whole time. Never concede.)

Just like there are endless books to read and a wide breadth of genres to explore, there are an infinite number of lessons to learn within climbing. Even if you know that the lesson in front of you is one that you should learn, it might not be the right time for you. In the same way that you might go through phases of feeling connected to specific book genres like non-fiction, fantasy, or biographies, you can also be most in-tune with certain genres of climbing lessons like movement, mindset, balance, or power. Lean into those times when learning comes naturally regardless of whether it’s the “best” thing for you right now.

Forcing yourself to read a genre that you’re not connecting with rarely leads to a good experience. The same is true in climbing development. Learn to appreciate the phase that you are in right now. You’ll find that learning and progress happen more naturally and the lessons stick better.

Eventually, this current genre of climbing will no longer hold your interest. As that happens, check back into those other genres that “weren’t for you” earlier on and see if it’s their turn now. The more you can make learning resonate with who you are and where you are at, the more enjoyment you’ll get from the process, and the more improvement you’ll see in the long run.

Despite being constantly present and often the reason we fail, Rhythm is the most underrated of the Atomic Elements of Climbing Movement.

Long-time friends Nate and Ravioli Biceps discuss lessons they’ve pulled from video gaming that can help inform our climbing.

There’s A LOT of great information out there on how to climb harder. But it’s tough to sort through…

Short climbers are good at getting scrunchy, and tall climbers are good at climbing extended, right? Wrong.

One of the most common places things start to fall apart is at the very beginning of the move.

We know spending time on a finishing link is smart tactics for hard climbs. So why not apply the same concept to individual moves?

Learning when and how to compensate for a weakness is a skill. And skills need to be practiced.

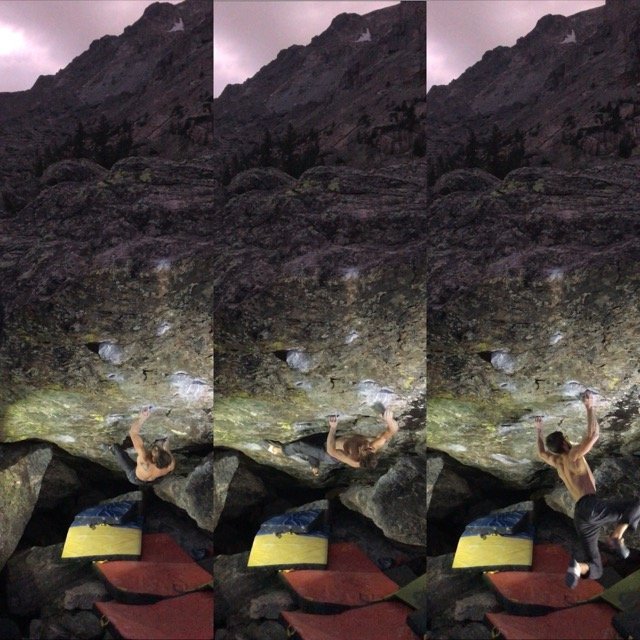

Lowball boulders, while not as proud, can still teach us new movement, new ways to utilize tension, and force us into finding new techniques.

I never thought I’d be recommending this, but some of y’all should be putting less effort into becoming technically better climbers.

Training principles are important, but when they creep into performance, your climbing will suffer. Nearly every time.

We have become collectors of dots. But there’s one major thing that happens when we connect dots that is entirely lost in mass dot collection: critical thinking.

Do you really have terrible willpower? Or are you surrounded by distractions and obstacles?

You have a climbing trip coming up. The rock is different. The style is different. Your pre-trip time is short and the number of days you’ll be climbing, even shorter…

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

Discussion around grades can be so polarizing that many of us avoid the topic.

Climbing starts off as this self-feeding cycle that has you wishing you could climb seven days a week. What happens when this cycle stops bringing improvement though?

Use strength to leverage every other aspect of your climbing, not replace them.

If everything you do is a finger workout, then when do your hands get a chance to recover?

There is a common theme between a grilled cheese sandwich and good training advice.

The more accurately we define our problems, the more approachable it will feel to find solutions.

Maybe the most understated way of getting better is to build fallback successes into your plan.

How much time should climbers spend becoming more well rounded vs. improving their strengths?

As cool as assessments and standards are, they can easily leave people settling for “good enough” when they have the potential to do much more.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.