Should Climbers Be Well-Rounded?

How often do I actually need to dyno?

How good at slab do I really need to be?

Why should I spend so much time on steep boulders if all I want to climb is techy routes?

A question that most climbers arrive at eventually (usually the threat of slab climbing initiates it) is how much time should they spend becoming more well rounded vs. improving their strengths.

If someone who has been climbing for several years and already has a decent base of experience and skills only wants to be good at a single style, wouldn’t it make sense to only specialize in that one thing? At face value, the answer seems like an obvious “yes”, but there are a few things to take into account when considering if now is a good time for you to become more well rounded vs. specializing.

There are three big advantages to diversifying your styles.

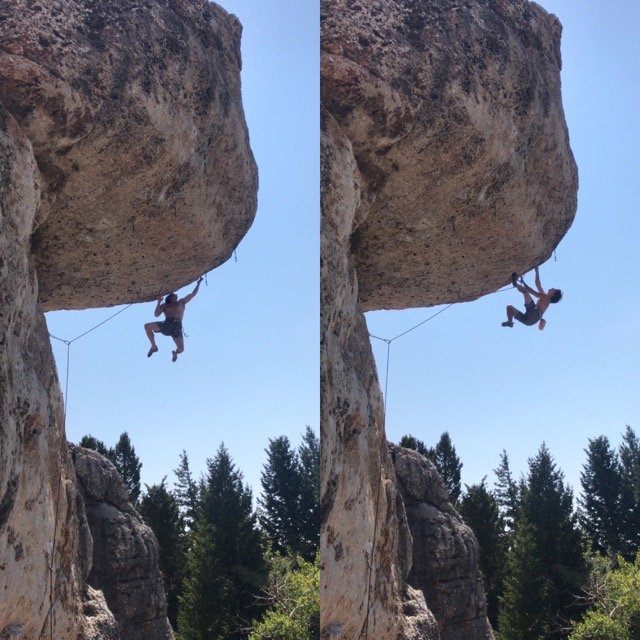

First, many of these skills we tend to avoid have a broader application to climbing than we realize. I can’t count the amount of times I’ve used crack climbing techniques on boulders and sport climbs. It’s not something I ever thought I needed, but those skills have transferred to my everyday climbing style.

Slab climbing, hard mantels, and offwidth climbing all teach a level of patience and composure that you can carry with you into almost any climbing situation.

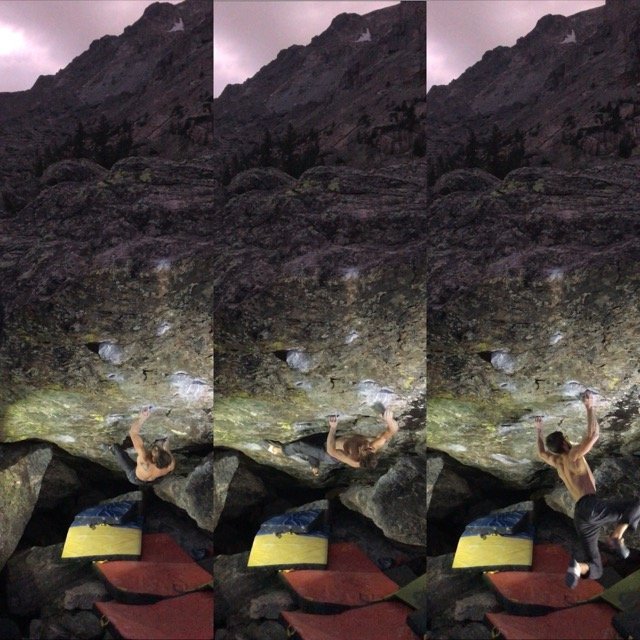

The second advantage to becoming more well rounded is that you reduce the occurrence of “personal cruxes”. People with significant holes in their repertoire often encounter “personal cruxes”, these sections of boulders or routes where seemingly no one else seems to fall except for them.

Dynos are dumb until there’s a v-easy dyno at the end of the route you want to do and you can’t come close to it even though it’s not supposed to be hard. Slabs are stupid until that big steep dream-route you want to do has some 5.11 “victory climbing” to the anchors and you’re too intimidated to even try it. It’s completely normal to find a wide array of styles across any route or boulder you want to try. As long as you don’t have any seriously glaring weaknesses this might not be an issue.

Handjaming as a sport climber seems like an unnecessary skill until the redpoint crux of your project revolves around it

Lastly, as you diversify your climbing style, you might realize that you’re really good at or really enjoy something you’ve never tried before. I used to think my best style was steep overhanging endurance routes. With that being my specialty, it’s also what I enjoyed the most. That changed when I decided to spend a full year focusing on technical sport climbing in the New River Gorge. I thought it would be a brutal year of working my weakness, but it turned out that this style suited me better than steep climbing ever did. I had never given it a chance before, but techy, slightly overhanging to vertical sport climbing quickly became my favorite type of climbing. I still had plenty to learn, but this was the most that I had ever connected with a climbing style. Had I not decided to step out of my initial comfort zone of steep endurance routes I never would have found that out.

If you can become well rounded enough to enjoy the broad array of experiences that climbing offers, and not fail on your projects because of easy to learn skills then you’ll be in a good place. Who knows, with a little time you might even start to enjoy those styles you’ve spent years avoiding.

Long-time friends Nate and Ravioli Biceps discuss lessons they’ve pulled from video gaming that can help inform our climbing.

I never thought I’d be recommending this, but some of y’all should be putting less effort into becoming technically better climbers.

Do you really have terrible willpower? Or are you surrounded by distractions and obstacles?

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

Discussion around grades can be so polarizing that many of us avoid the topic.

Climbing starts off as this self-feeding cycle that has you wishing you could climb seven days a week. What happens when this cycle stops bringing improvement though?

Use strength to leverage every other aspect of your climbing, not replace them.

If everything you do is a finger workout, then when do your hands get a chance to recover?

There is a common theme between a grilled cheese sandwich and good training advice.

The more accurately we define our problems, the more approachable it will feel to find solutions.

Maybe the most understated way of getting better is to build fallback successes into your plan.

How much time should climbers spend becoming more well rounded vs. improving their strengths?

As cool as assessments and standards are, they can easily leave people settling for “good enough” when they have the potential to do much more.

Being able to quickly recognize familiar sequences is a crucial ingredient to harder climbing.

It’s far more comfortable for us to blame ignorance for our lack of progress than it is to blame our own efforts.

Once you learn the power of good tactics it can be hard to step away from them.

Of all the people that I spoke with this year who were stuck in plateaus, many of them had the same thing in common: they climbed and trained alone.

The belief that you are getting better at climbing is one of the most important ingredients in actually getting better at climbing.

How many times have you gone up a route and felt overwhelmed, only to look back and realize that it’s not as intimidating as it initially seemed?

Most of us go into a training plan or an outdoor season with an expectation, but expecting results can make us brittle when problems arise.

Whenever there is a training article online or some tidbit of knowledge on social media, it’s important that you consider the context.

At a certain stage in climbing, the hand and foot beta you use stops being the deciding factor in whether or not you are successful.

The intermediate climber’s problem with perception starts to arise when they can’t recall all of the solutions they have attempted during the problem solving process.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.