Skills of Perception: Part 3

If you haven’t read parts 1 and 2 of this series yet, you can check them out here:

Part 3: Paying Attention to Your Body

At a certain stage in climbing, the hand and foot beta you use stops being the deciding factor in whether or not you send. At that point you need to shift your attention from solely focusing on the macro beta of lefts and rights to the micro betas of tension, position, speed, focus, intention, and things of that nature.

You might be able to remember every nuance of your beta at this point in your climbing career, but how much do you recall about how your body felt during each attempt? This can make a massive difference when trying to decipher a crux move.

-Were you in balance when you went for the move?

Or were you rushing to go for it? Ending up out of balance when you stick a hold often comes from being out of balance when you initiate the move.

-Where were you holding tension in your body?

Did it feel like your core and upper body were fully engaged, but you can’t remember how your legs felt? Are you feeling effort in the places you want to be? If you’re getting a bicep pump while slab climbing that might be a sign to get more weight onto your feet.

-Were all of your limbs contributing to that movement?

What was each hand and foot doing? It’s normal for us to only focus on two to three points of contact and completely forget to incorporate the other ones.

-Which hand and foot was taking the most weight?

Are you using the holds in a way that will give you the best chance of doing the move or are you defaulting to what feels comfortable? When we get a good hand or foothold we like to use it as much as possible. If gone unchecked, this can quickly turn into underweighting the other holds, putting ourselves into a worse position, and making the move harder.

-What were you focusing on when you went for that move?

Did you believe you were going to stick that move when you went for it?

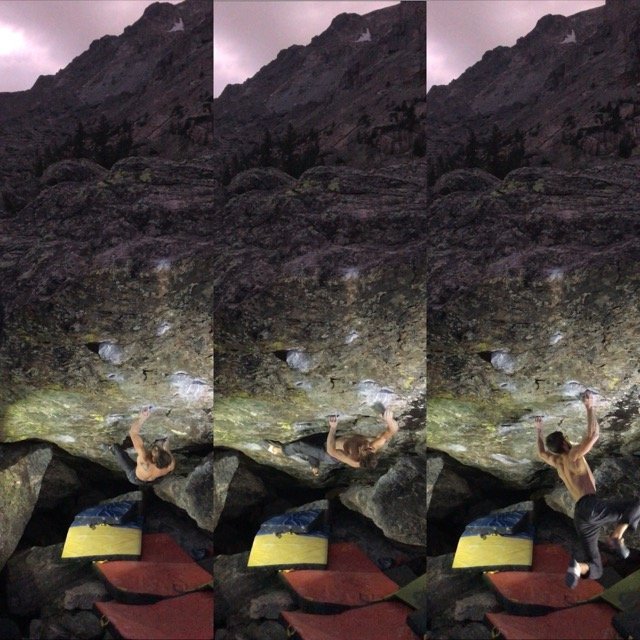

-How fast were you moving when you went for that hold?

Speed is an underutilized tool in problem solving. When you struggle with a move it can help to try it going slower and faster. You might find that your default speed is what’s holding you back from sticking it.

Interestingly, I often see climbers who consider themselves to be weak regularly moving too fast on big or powerful moves. They have convinced themselves they need to always give 100% for power moves. While this can initially bring success, it also means they miss out on developing an internal dial for intensity. When they start slowing things down they find that they are better at big moves than they were when going with 100% power.

-Did you get to the destination hold in control?

We love to blame our contact strength for us not sticking big moves to bad holds. While that does contribute to our failure, it’s important that we try to arrive at crux holds in as much control as reasonably possible. If we can let our full-body strength and coordination do most of the heavy lifting for us then we won’t be as limited by our contact strength.

-Which hand or foot came off of the wall first when you fell?

If people’s feet were always the last thing to come off of the wall when they missed a move we’d see a lot more backflops off of boulders.

Read that again.

-When you fell, which direction did you fall away from the wall?

This can tell you so much about your positioning and whether or not you were in balance.

-How hard were you trying?

Not every crux move is a 100% “eyes closed, everything flexed” kind of move. It’s possible to try too hard on a move. More often though, we can get stuck giving half-hearted efforts at a hard move in hopes that we’ll unlock some perfect beta or subtlety that lets us succeed without trying too hard. If you’ve been trying a hard move for a little while and aren’t sure what to try next, try trying harder. It ends up being the answer more often than we like to admit.

Climbing is a never-ending game of chasing improvement. Get stronger, get fitter, improve your tactics, become mentally stronger, and continue to eke out gains from every attribute that you can. As you do, make sure to continue advancing your skills of perception. Learning to spot patterns in why you fail to do a move can be one of the best ways to know what skills and strengths you should develop next.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.