Breaking Beta | Does Stretching Result in Power Loss?

In this episode, Kris and Paul discuss a hotly-debated topic - not just in the climbing world but the greater athletic community:

Acute Effects of Static Stretching on Muscle Strength and Power: An Attempt to Clarify Previous Caveats

authored by Helmi Chaabene, David Behm, Yassine Negra, and Urs Granacher; published in Frontiers in Physiology in 2019.

They’ll attempt to determine whether or not stretching in your warmup is what’s costing you that last bit of power you need to send the proj, or if it’s exactly what you need in order to execute that heel-hook-next-to-your-ear crux move without pulling a hammy. Tune in to find out what data on the topic is legit, and what might be a bit of a...well, you know.

*Additional studies/resources mentioned in this episode:

Factors Affecting Force Loss with Prolonged Stretching authored by David Behm and Duane C Button; published in the Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, 2001.

Stretching the Way We Think About Athletes, TEDx Talk by Dr. David Behm

New episodes of Breaking Beta drop on Wednesdays. Make sure you’re subscribed, leave us a review, and share!

And please tell all of your friends who spend their warm up time telling you that you should stop doing any stretching in your warm up that you have the perfect podcast for them.

Got a question? Comments? Want to suggest a paper to be discussed? Get in touch and let us know!

Breaking Beta is brought to you by Power Company Climbing and Crux Conditioning, and is a proud member of the Plug Tone Audio Collective. Find full episode transcripts, citations, and more at our website.

FULL EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 00:05

You understand what you have to do? You can never talk to anyone, right? I mean ever. Understand?

Yeah.

I found this stuff on the internet. Takes days to kick in. Just keep quiet and this won't ever come back to you. You okay with this right? Just think of it like it's same thing as always, you're just delivering some hamburgers.

Kris Hampton 00:29

I don't even know what that means. But I just had to put it.... we found it on the internet and it's like delivering hamburgers. Alright, we are here today to talk about one of the most cited facts in all of sports science and I'm "facts", air quoting there, is that you lose power when you stretch. I hear it all the damn time. If I'm if I'm stretching for 10 seconds at the crag, somebody is inevitably going to pipe up, "You're gonna lose all your power." and I'm like, "Okay, maybe not." It's become this

Paul Corsaro 01:06

I mean why would you even warm up? You know, predators don't warm up to chase the rabbit or some shit, right?

Kris Hampton 01:12

Haha exactly.

Paul Corsaro 01:12

Why would you warm up and stretch?

Kris Hampton 01:14

And no one's ever seen a dog stretch before

Kris Hampton 01:17

Except for all the time. It's become this strangely like polarizing thing with even some of the people who who actually do follow science getting stuck in this really dogmatic view and I think that it's just the nature of talking about stretching and flexibility. Everyone has their own dogmatic side of it that they're on, so we're gonna try and shed a little light on it here, starting with a paper called "Factors Affecting Force Loss with Prolonged Stretching". And this is from the Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology in 2001. Authors are David Behm and Duane C. Button. Behm and Button, that sounds like a great law firm. Purpose of the study was to investigate factors underlying the force loss occurring after prolonged static passive stretching. Any thoughts from you going into this initially? Like, before we even get into this paper, what was your thought when it was suggested that we talked about stretching?

Paul Corsaro 01:17

Never

Paul Corsaro 02:25

Uh, so... what was it? About... I don't know, five to eight years ago, this idea first started getting or its when I first noticed this idea that like, you know, you lose... people really talking about how you lose power when you stretch, so you probably shouldn't stretch before you lift or do anything that requires force generation. And, you know, everything that was getting thrown around was all absolutes, which means I immediately stopped paying attention to it, because that's stuff just annoys me. Like, you know, I, in all my in my studies and, you know, the, what I do on the outside end to keep growing as a coach, like you see these papers cited and I've seen, you know, this paper's main point being shared along with some other ones that maybe we'll get into later. But honestly, I never read this paper, because the amount of dogma that was thrown around just annoyed me. So yeah, so I was actually, I was interested to dive into this one and really look into it some.

Kris Hampton 03:18

Yeah, same. Alright, let's get into it.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 03:21

You clearly, don't know who you're talking to, so let me clue you in.

Paul Corsaro 03:25

I'm Paul Corsaro.

Kris Hampton 03:27

I'm Kris Hampton.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 03:28

Lucky two guys, but just guys, okay?

Paul Corsaro 03:32

And you're listening to Breaking Beta,

Kris Hampton 03:34

Where we explore and explain the science of climbing

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 03:38

With our skills, you'll earn more than you ever would on your own.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 03:43

We've got work to do. Are you ready?

Paul Corsaro 03:46

I'm ready. How about you, Kris?

Kris Hampton 03:50

I'm exceptionally ready to talk about flexibility, actually. I know there are a lot of people, regardless of whatever evidence there is, who are going to get angry and I kind of just like that. Let's first jump into the methods here.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 04:08

In a scenario like this, I don't suppose it is bad form to just flip a coin.

Kris Hampton 04:15

Why don't you tell us a little bit about the methods here, Paul?

Paul Corsaro 04:19

Right. Cool. So for the methods, they originally had 16 subjects. It looks like four of them were disqualified, because they weren't able to activate more than 80% of their quadriceps, which, you know, I think is interesting, to say the least. But anyways, moving on, so they had 12 healthy, active male subjects from a university population. Again, no female subjects, which is another interesting choice.

Kris Hampton 04:43

That that seems to be kind of rampant in a lot of the studies we end up looking at.

Paul Corsaro 04:49

Yeah, I, you know, I wonder if because, you know, this one's from 2001, so maybe as we get later on, and more recent, maybe we'll see more of a balance per se, but yeah, that is something I kind of noticed. I've got a big F with a question mark there in my notes. So, yeah, that was surprising to me. LIke you would think that for a study to get as much validity and relatability to the outside world, you'd probably want to include females as well, but I don't know.

Kris Hampton 05:17

Right.

Paul Corsaro 05:18

But anyways, so, you know, the median age was a...they were from 20 to 43 years old. They're all volunteers. So six of them did a, were a control group, so they didn't do any stretching before or after the testing. And the other six were the experimental group where they would test and then do the stretching and then do the testing again.

Kris Hampton 05:41

And what kind of what was what did the stretching look like that they were doing?

Paul Corsaro 05:44

So they did four different stretches for five sets. Each stretch was held for 45 seconds and they rested 15 seconds. When you add that up for all five sets, that's about 20 minutes of time under tension in the stretch. So they did a standing quad stretch, which is basically you know, you're standing up, hands on the wall, grabbing your foot and pulling it back towards your butt. They held that for 45 seconds, rested 15 seconds. Then they also did the hurdler stretch, which, you know, these stretches also do kind of show when this study was done, because I haven't seen some of these done in quite a while.

Kris Hampton 06:18

Haha right. That hurdle stretch was all of my high school years.

Paul Corsaro 06:21

Likewise. Yeah, high school, all that. Yeah, so you know, you're sitting down. Your left foot or left foot, for example, is back behind you at 90 degrees. Your front, your right foot is straight out in front of you. So all of these seem to be targeting the quadriceps overall. They had a kneeling hip extension stretch, which is you're basically on your knees. Your hands are behind you on the ground, and you'd extend your hips towards the ceiling to stretch the quads. And then you had an assisted quad stretch, where you would lie down in a partner would help stretch that quad muscle, so.

Kris Hampton 06:54

Nice. This... all these stretches actually sound more like 1990 than 2001.

Paul Corsaro 06:59

They are the throwbacks if you will, and then they did some testing. And this happened about... this happened five minutes after the stretching protocol was over. So the first thing they tested was the muscle's twitch properties, so just a short fast contraction. And then after they tested the twitch properties, after at the five minute mark, from within the six to 10 minute mark, this is kind of varied a bit and they randomized it per participant, they tested three voluntary contractions, which is basically just a knee extension against a force measurement device. So they measured how strong that knee extension force was and they did three of those contractions as well as two "tet-nick" or tetanic contractions. I'm sure someone can correct me on how to pronounce that, but which is basically just a longer sustained contraction. And it's also kind of crazy, they minimize that to 300 milliseconds, because a pain threshold cut things off after that.

Kris Hampton 07:57

Oh, wow,

Paul Corsaro 07:57

So that sounds like a pretty heinous test in my book.

Kris Hampton 08:00

Yeah.

Paul Corsaro 08:01

But so what they did, they did those two tetanic and three voluntary contractions within that six to 10 minute window, so there's about a minute rest in between these tests. And they just measured the force or the contraction intensity, to see if stretching changed any of these measures.

Kris Hampton 08:20

Yeah, and I think, you know, this is this is where we started. And, and I think a lot of the listeners out there who are, you know, really listening and paying attention will say, "Oh, but you're only looking at this long, you know, prolonged stretching. What about all the other types of stretching?". And this study was 2001. There's been 20 years of research since then. And science is smart, you know. We, as the reader, need to exercise some of that as well and in the case of flexibility, the question of "Does it help our performance?" is really broad. It requires looking at many smaller questions, including the duration of stretching, this is just one of the possible durations, the timing of the resulting performance, which they're, you know, they're waiting five minutes here and then the type of stretching and, and there are all sorts of things you can manipulate in this study, and no single study is going to have have all of the answers. And I think that's really important to recognize, and that's why we started with this paper. Just to point out this is one tiny aspect in answering a much larger question. And good researchers will look at one small question at a time in order to answer that bigger question and as such, we can't simply look at just one of the thousands of papers conducted on stretching to find the answer. So we're going to pivot here and instead of looking at this one little study, since we have this giant body of research, what we're going to do is go look at a systematic literature review instead. And the title of this is "The Acute Effects of Static Stretching On Muscle Strength and Power: An Attempt to Clarify Previous Caveats" from the Frontiers In Physiology Journal 2019, so much more modern day. The authors are Helmi Chaabene, Yassine Negra, Urs Granacher and David Behm, same researcher from the study we started with here, and he's one of the superstars of, of flexibility research. He's got a couple of TED talks I think. One in particular, that's really enjoyable and if you're interested, you should definitely go check that out. He's probably done more flexibility research than anyone else on the planet.

Paul Corsaro 10:55

I think it's important to note too, that he's still doing, he's looking into the effects of stretching, on static stretching on muscle strength and power, which, you know, was the study he published in 2001. This is 18 years later, and he's still exploring it. So everyone who's taken a paper from 20 years ago and being like, "Yep, this is it. This is the answer.", like the person who published this paper is still trying to figure out the nuances, still trying to dial in and understand what is the actual truth behind all of the results they're getting, so.

Kris Hampton 11:25

Right.

Paul Corsaro 11:26

It's always evolving.

Kris Hampton 11:26

Which is how science works, you know?

Kris Hampton 11:29

Yes. 100%.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 11:30

Yeah science! Yeah science! Yeah science! Yeah science!

Kris Hampton 11:36

Wow, it just really wanted to be all about praising science right there. I'm just gonna leave that in haha.

Paul Corsaro 11:44

Jesse was psyched haha.

Kris Hampton 11:45

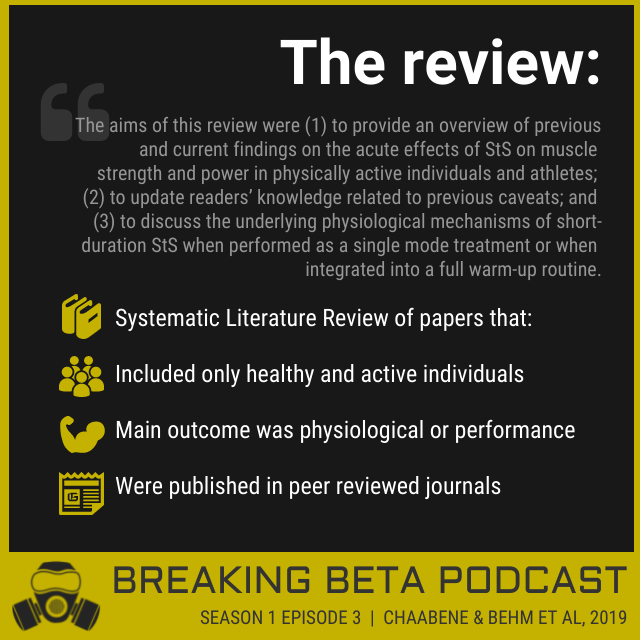

Haha. So the purpose of this review is to summarize previous and current findings on the acute effects of static stretching on muscle strength and power performances and two, to update readers knowledge related to previous caveats, and then three, to discuss the underlying physiological mechanisms of short duration static stretching, when performed as single mode treatment, or when integrated into a full warm up routine. And I think that's really smart. You know, how often do we just go straight from static stretching, right into the performance? It's far more likely that in the field, in real life, it's going to be part of some sort of a warmup.

Paul Corsaro 12:28

Mm hmm. Yeah, that's where you're gonna see it the most. I'm very, very rarely are you seeing someone doing an intensive stretching protocol right before you know, an exercise, and then they're gonna go do some more exercise and then okay, before this last set of strength work, we're gonna do some more stretching, so

Kris Hampton 12:43

Right, right.

Paul Corsaro 12:44

It's gonna be a little bit more relatable in the real world.

Kris Hampton 12:49

Alright, and let's, since we've already been through this with the other paper, let's just real quickly look at the kind of the basic methods of a review, just for people who aren't aware. A review essentially takes a look at the entire body of research. They do put some qualifications on that. And this one, in particular, included studies that examined the acute effects of static stretching on subsequent strength and power performances. And only studies that addressed a research question related to those acute effects of, of static stretching on strength and power performancesnd a included healthy active or competitive individuals were included, and that the main outcome was a performance or physiological measure. So it sounds to me like what they were trying to do was make it more real world.

Paul Corsaro 13:44

Yeah, a couple other things I think are important on the methods here too, is they did use certain databases, so Medline Science Direct and Google Scholar. I'm sure if you used a different database, or different method of pulling papers, maybe you'll get a different combinations of those. And they actually use keywords to pull some of these papers too. So they used keywords such as static stretching, chronic effects, physical performance, strength, power and injury. And then once they got that big pool of papers from those keywords, then they use that criteria to kind of narrow down that list of papers to kind of get the body of evidence that they used to make the rest of the review.

Kris Hampton 14:22

Right. Did you see anywhere.... I looked, and then I went online and looked and I couldn't find an answer to this, how many papers were included in this study?

Paul Corsaro 14:31

I didn't see that. I looked around. Usually they have that.

Kris Hampton 14:35

Yeah, I was surprised not to find it.

Paul Corsaro 14:36

So I'm not sure if this is a meta analysis. I think they go a little more in depth with some of those formats, with the meta analysis format, with like, you know, how many papers and they have like the n equals number and all that, but I think they just for this one, they just gave us the search methods and inclusion criteria.

Kris Hampton 14:54

Yeah, and I know they they cite 55 other papers in here, several of which are actually also literature reviews and some of those reviews do include several hundred papers. So there's a lot of information just kind of all bunched together here, which has its pros and its cons, you know. On one hand, we get to see the results from a lot of different papers, a lot of different methodologies and people coming up with, with different but similar results. On the other hand, it's, we don't really get to see the details of any of those individual papers to determine for ourselves whether it feels like a good study or not, or if they might have missed something that pertains to real world application rather than just in the lab.

Paul Corsaro 15:54

Yeah, so how I'll usually use review papers, if I'm trying to dig into a subject, is I'll read the review and then I'll pick out a couple papers out of you know, the short blurb they give about a paper or review, that seems interesting to me and I feel like maybe we could go down that rabbit hole, and then I'll go down and find the find the where it's cited in the references, and then go try and find that paper, and then read that paper until I get tired or run out of time.

Kris Hampton 16:20

Haha yeah. You could almost you could almost go forever here. You know, there are just so many papers that reference so many other papers. And it's really neat to, now that you know, we've gotten into some of these climbing specific studies, it's really neat to go back to a subject that has just thousands and thousands of papers published on it.

Paul Corsaro 16:44

Because there's not that for climbing yet.

Kris Hampton 16:46

For sure. Yeah, and here's an interesting thing. Stretching, like I said in the beginning here, is has become this really dogmatic, polarizing thing. No one can really agree on a lot of the aspects of this and there are thousands and thousands of research papers, you know, over the last several decades. One climbing paper pops up saying something and all of a sudden, it's fact in a lot of people's eyes and that's just not how science works.

Paul Corsaro 17:16

And you know, we'll probably get more and more of the cloudy, general guidelines as we move on into the world of climbing science, I think, I hope or maybe not, maybe everything will be clear and maybe there'll be only one way to train and then we won't have to make any decisions and everyone's gonna get really strong and it'll be great.

Kris Hampton 17:36

Yeah, that would be fantastic.

Paul Corsaro 17:38

Yeah.

Kris Hampton 17:39

Not how I think it's gonna work, though. All right, let's, uh, let's take a break and we'll be right back,

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 17:43

Please. Alright, I really need a break here. Okay.

Lana Stigura 17:49

You're listening to this super nerdy podcast, so I can only assume that you're interested in improving your climbing. Well, good news, you're in luck. Yes, we have training options for nearly every level climber in nearly every situation. From general prep to fully custom, from ebooks to weekly plans delivered via mobile app, visit power company climbing.com/breaking beta for more info. And while you're there, check out Kettlebells for Climbers 2 now available as either an e book or a proven plan, the follow up to our wildly popular Kettlebells for Climbers plan, it started so many climbers down the path to being stronger, better prepared and more athletic.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 18:23

So go back to work for Christ's sake. Okay.

Kris Hampton 18:27

All right, we are back from the break. And we are ready to jump into what the results of this review were right here to sit in judgment.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 18:38

But the thing is, if you just do stuff, and nothing happens, what's it all mean? Whatever, whatever you think supposed to happen, I'm telling you the exact reverse opposite of that is gonna happen.

Kris Hampton 18:57

So for me, one of the very first things that jumps out is that they point out that this this all all of this research comes down to dose and response. And this is, I mean, honestly, this is the case with all training modalities. So even if you're a diehard, no stretching fan. I mean, if that's what you preach. If you have the first clue about how humans respond to training, then you have to recognize that not all doses of stretching will result in the same response. And I think that's a thing that gets overlooked really often.

Paul Corsaro 19:37

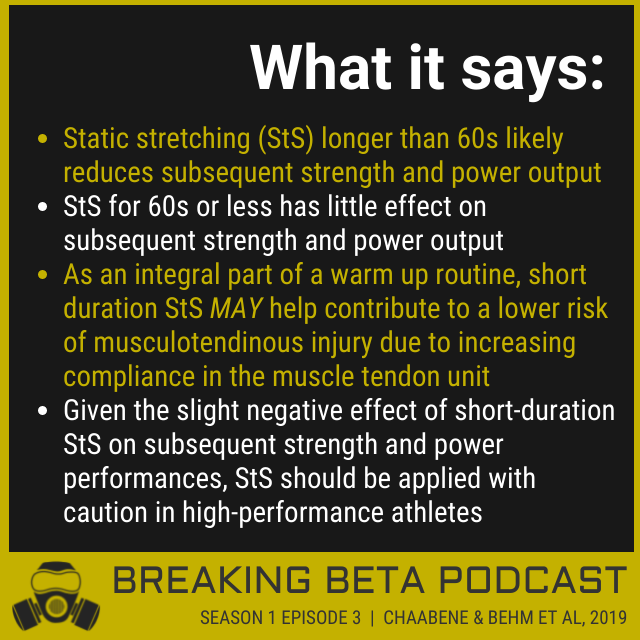

Yeah, I think when we consider the dosing of stretching, as we go through this review, they first looked at the first wave of papers that came out that kind of were saying, Hey, don't stretch for you do strength and power and they looked at the dosage of that. It seemed like most of those stretches were 60 seconds or more, right? Those seem to be the stretch and if you get above that 60 second mark, that's what really appears to start dropping that strength and power in a significant way.

Kris Hampton 20:05

Yeah, that seems to be one of the big findings here. And some of the physiological mechanisms of that long duration static stretch, were that it lowered muscle activation. And it increased the muscle tendon unit compliance, which negatively affects the rate of force development, but also has some pros in that, you know, there's there's some literature saying that it's better for force absorption. And there's the potential that it could reduce injury. I don't think there's any clear lines being drawn there yet. But a lot of people are making that, that hypothesis.

Paul Corsaro 20:46

Yeah, I think the big thing I got from this is really the stiffness of the muscle tendon unit really does play a big role in performance, especially with plyometric activities. So, you know, if we're talking about powerful movement, climbing, we'll keep it climbing related, but there's a bit of a stretch shortening cycle there to where you need to like load up and explode or catch a hold and move on to the next one. And that's all stiffness there, you know, the muscles are more so the tuners of the connective tissue, in that perspective, where the connective tissue is really the thing that is storing and releasing the energy. So if we increase that compliance, there's gonna be a bit more inefficiency in the storage, which could be why we're seeing a little bit less, or why we're seeing that decrease in power production after those longer duration stretching, because you know, that spring is a little slack, a little more slack, if you will.

Kris Hampton 21:34

Right. Something I thought was interesting that came out of a study that... one of the rabbit holes I went down, I honestly can't remember which rabbit hole it was, and I didn't write it down, was that when they looked at lifters, it showed about a 5% drop in force. When they looked at runners, it only showed about a two or two and a half percent drop in force. And that made me curious as to I wonder if it would show up in climbers, like stretching your fingers or stretching your shoulders? Is it going to show up at all? I don't really know. And I don't think we can make a very accurate guess as to that until there are studies that are looking at that.

Paul Corsaro 21:36

Could you make an inaccurate guess?

Kris Hampton 22:20

I can make, I can make an inaccurate guess.

Paul Corsaro 22:27

What would you say?

Kris Hampton 22:27

I am really making lots of inaccurate guesses. I would think there is a small percentage drop in the stiffness of that muscle tendon unit and I would assume you would lose a little bit of force. However, I don't know that we ever use 100% of what we have available anyway. And, you know, if we look at say a 5% drop, one of the things from the David Behm TED Talk that he points out that I think is really interesting, is that if you're Usain Bolt, a 5% drop is big, you know, but he's an elite athlete. A 5% drop might have cost him first place and put him into 16th place in the Olympics, but he's using 100% of what he's got. It's extremely rare, if ever, that I'm using 100% of what I've got, so I'm not sure it makes a difference for me.

Paul Corsaro 23:34

Yeah. And I think, you know, especially if we're looking at this, maybe in the aspect of going into a training session, I don't think it's gonna affect it all that much because you're not trying your lifetime limit project where you know, you need 100% of everything you have physiologically.

Kris Hampton 23:48

Right.

Paul Corsaro 23:49

So I think, you know, if this is if you this was if you stretched for over 60 seconds to begin with anyway, right? So yeah, so I think yeah, maybe they've statistically significant results, but I'd be interested to see how they show up in a real world situation in our sport.

Kris Hampton 24:06

Yeah, same. And like you said, that's just the long duration static stretch. When they looked at those shorter duration static stretches, they didn't significantly alter muscle activation.

Paul Corsaro 24:18

In almost every review, there was like four or five complete other reviews they pulled into this this review that all pretty much said if you stayed under 60 seconds, you're pretty much good. You weren't gonna have any statistically significant decreases.

Kris Hampton 24:31

Yeah, same with the muscle tendon unit stiffness, didn't significantly negatively affected there. So it seems like a short duration static stretch is totally fine.

Paul Corsaro 24:45

And they also said if you used it during a warm up routine, so maybe stretches in conjunction with some other tissue temperature warming activities, some general movement work could actually be a net positive in that we're warming up the tissue temperature

Kris Hampton 25:00

Right.

Paul Corsaro 25:01

Helping with those muscle physiological qualities along those lines. So I think when they came down to it at the end of this review, the overall recommendation was that yeah, keep your stretches under 60 seconds and incorporate them in a well rounded warmup protocol and you're probably in a great spot.

Kris Hampton 25:18

Yeah, one of the other things I saw on here that was super interesting is that there's a 2018 study from Blazevich, I believe he's Australian, that showed positive psychological benefits. The the people in the study thought they would perform better. They believed it, irrespective of the stretch type. So even if they were stretching for 60 seconds, 30 seconds didn't matter. They believed they were going to perform better and that's a very key part of performing well, for almost all of us.

Paul Corsaro 25:54

100%, you know, in a study the placebo effects and the reason that they have to control for it is because it's actually effective, and it changes things.

Kris Hampton 26:01

Right.

Paul Corsaro 26:02

So you know, from a performance perspective, if you're going into it mentally positive and feeling confident, you know, the odds are tipped more towards success to start out with.

Kris Hampton 26:10

Yeah, there was there were a couple things in here I was curious about. Maybe you understand better than I do. They mentioned there was a 2019 study from Conrad et al, that after five minutes of static stretching, MTU stiffness was decreased but then after 10 minutes, it was back to normal. So it sounded like it decreased the stiffness of the MTU, made it more compliant, but then 10 minutes later, it was all back to normal. However, they also mentioned that all of the time stretches resulted in increased range of motion, but they don't say for how long and I was curious if you knew more about that or if you saw something in there that said, range of motion is increased indefinitely, or it's increased for those five or 10 minutes or do we know?

Kris Hampton 26:14

I don't think we really know from that. I think we'd have to just go with what they said w theirith timeframes, you know. They tested it then, I'm not sure where we go to if it's like, yeah, permanent or, you know, multiple hour long change in that range of motion. I think we just got to go with what they're saying in those those timeframes. I'd have to read that actual study to come at it from a bit more informed point of view, I think.

Kris Hampton 27:33

Yeah, same. There are a lot of studies here to read. I'm just going to default to David Behm most of the time since he seems to be involved.

Paul Corsaro 27:41

Yeah he's a superstar.

Kris Hampton 27:42

Yeah. Anything else in these results that you found surprising before we jump into application and how we might use it?

Paul Corsaro 27:51

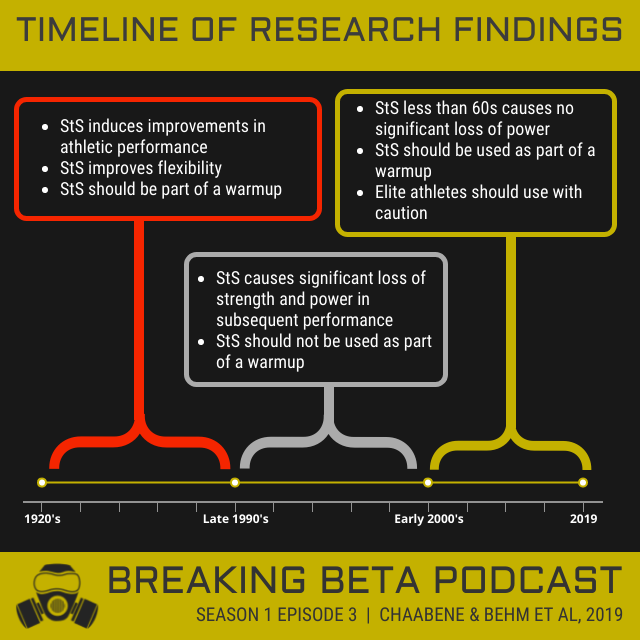

Not particularly. I thought it was a well done review. I think it came with some really good practical application. Like, you know, it's a review you read and as a coach, you're like, okay, this makes sense. This is a lot of information, but it's boiled down into, you know, a couple few actionable points, which what I really liked from a review. Like if I'm gonna spend, you know, an hour or so reading a review, I'd like to come out of it with something that I'm going to use almost immediately or like, feel pretty confident about and I think this study did that. It broke down, you know, the changes in attitudes over time from I mean, they even have a timeline here from the World War, World Wars all the way up into 2019. I thought that was cool. Where they showed how vast opinion swaps from side to side. So yeah, I think it was a really good review.

Kris Hampton 28:39

Yeah, I think that that timeline they show, I'm going to have it in our social media posts that you can see on Instagram as well. But that timeline is really interesting to me, because it's it's showing us how science works. They ask a question, they answer that question and then they're like, oh, but wait, what if we ask this question in a different way? And then they come up with different results and then they're like, what if we start combining these two questions and ask it in this way? And then they're coming up with new results. And they're, they're never just being super dogmatic about it and I think that's the, I mean, that's the scientific method. That's, that's how it should work.

Paul Corsaro 29:17

And you know, this kind of breaks down, which is also nice to read, it kind of breaks down how I apply stretching with the people I work with. I like to program a lot in super sets and, you know, tri sets, what have you, where, you know, we've got a big strength movement and we've got some mobility work or stretching thrown in, but we keep it short, and they're not just hanging out in a stretch for five minutes. But it's a great way to build that in and they can still lift hard after that. But they're feeling good. They're not just sitting there twiddling their thumbs possibly rushing their rest.

Kris Hampton 29:46

Right.

Paul Corsaro 29:47

And it just it fits really well with my model. So this also fits my biases quite a bit so that's maybe why I like this as well.

Kris Hampton 29:55

Yeah, yeah, I've gone back and forth on stretching myself, so I'm not sure I had a bias here necessarily. I just found it really interesting. And I, one thing I loved and you already mentioned that the study does this, but I love that at the beginning of the study, they say that a lot of the evidence can be really confusing for coaches and practitioners and that's the whole purpose of this study is to kind of make it less confusing for those of us who are using it.

Paul Corsaro 30:27

Exactly.

Kris Hampton 30:27

Alright, let's look at the application.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 30:30

All these little pieces, they are all part of the story, right? But they don't mean much on their own. But when you start telling me what you know, we start filling in the gaps. I'll have them in lockup before the sun goes down.

Kris Hampton 30:41

Alright, should climbers be stretching and how? What's that look like for you?

Paul Corsaro 30:47

Oh, yeah, I think it really just comes down to a case by case basis. If you feel you need it, or it makes you feel good, or you feel like it's part of your warm up, I think it'd be useful to do so. I'm not gonna go out and tell you that you need to stop doing what you like to do. I think some people may not need to stretch as much and I don't think that's an issue as well. I think, going with the guidelines from that review paper more so, if you're going to try hard later, or maybe you're about to jump on your project of the season, you know, the last couple days left, performance is critical, I probably wouldn't hang out in pigeon pose for three minutes before you jump on the boulder. That's probably not going to be the way to go. I think you know, if you look at the results from that first paper we're talking about, they did see some significant drops in that maximum voluntary contraction, you know. They dropped about 20 pounds or so if you had to do some rough napkin math, because they gave it in Newtons, but I think I figured it out. But yeah, it was 20 pounds drop, which was significant for the force generated in that knee extension. I think that was the important thing to take away from that first paper we were talking about. And that was a longer that was a longer stretch, so it showed more of that decrease in force, which could matter. But if, I think if you keep things short, stretching feels good to you and you're noticing range of motion improvements, I wouldn't stop.

Kris Hampton 32:13

Yeah, if you're you know, if you know that your project has a position that you have a little trouble getting into, by all means, do some, you know, short duration static stretching less than 60 seconds during your warm up. Make it part of a full warm up that include also includes dynamic stretching and sports specific warming up and I think you know that increased range of motion helps you get into that position. You're not experiencing a lot of force loss in that case, so it makes total sense to me that, that we would do it. And there is some conjecture, some hypothesis that it could reduce injury. Why not, you know, if it's not going to hurt your performance, why not hedge your bets toward that? I'm not going to say it will reduce injury, because we just don't know and the goal for me is performance. Iit's going to help me get into that position, and I'm going to perform better, great.

Paul Corsaro 33:15

We actually did a little... I, when I read this study a couple weeks ago, I just was thinking and playing with stuff in the gym. We actually did a little test/retest with someone where we set a challenging drop knee move on our spray wall, and I ran them through a circuit of short, 30 second, kind of dynamic stretches in and out of hip external and internal rotation, paired with some shoulder mobility drills, just kind of so we're not stretching the hips for 60 seconds or more. And they couldn't do the move in the beginning, stuck the move first try afterwards. There's a lot of other stuff going on there, so, but they did notice they felt stronger in the drop knee, so it could be useful.

Kris Hampton 33:54

Yeah, I mean, as I boulder harder and harder, as I try harder and harder things, they involve more extreme for me positions, and especially drop knees, you know, big high heels where my hips are going to be working at their limits. I absolutely am going to do short stretches so that I'm stronger when I get into those positions, or I can get into those positions easier, and then apply the strength that I have in those positions.

Paul Corsaro 34:26

Yeah, it makes sense to do that, I think.

Kris Hampton 34:28

Yeah. And frankly, you know, like I said during the results section, especially when it comes to stretching the lower body, I'm honestly not terribly concerned if climbers want to stretch, I mean even for the longer than recommended 60 seconds. You know, if they believe it helps, then great. And if if there's ever a time in climbing when we need 100% of the force we're capable of producing with our legs, I'm not sure what it is. You know if you're an elite sprinter or a jumper, sure. Climbers, it's pretty rare.

Paul Corsaro 35:03

Speed slab climbing.

Kris Hampton 35:04

Speed slab climbing. Hahaha I want nothing to do with that. Actually, I've done a little bit of that, strangely enough.

Paul Corsaro 35:13

Oh, yeah?

Kris Hampton 35:14

Ray and I used to race up this slab in Vedauwoo. We used to time each other to see who could climb it the fastest.

Paul Corsaro 35:20

You should have streched before. Or you shouldn't have stretched before. Sorry. Sorry.

Kris Hampton 35:22

Shouldn't have stretched longer than 60 seconds, I might have screwed myself. And one more time, I feel like I just have to say this, that this is a great example of science working. One research paper, one study is not the full depth of science working. This is how it works. Up until the 90s, the advice was that everyone should be using static stretching as part of a warm up program. When I was in like my freshman year of high school, we would stretch for like an hour before track, you know. I was a pole vaulter. I'd stretch with the sprinters, tons of hurdle stretches, lots of just laying on the track stretching. But that was the 90s and then from the 90s to the early 2000s, the advice was to not use static stretching as part of your warmup. And now we're combining those things that they learned and saying what we learned here.

Paul Corsaro 36:21

Yeah, I think, yeah, I think it just shows how things change. And I think this is a great example of how one paper needs to be considered in context of the entire body evidence. That's where reviews come in really helpful. So I thought this is a fun thing to do where we took a paper and then looked at the review, too, and saw where that puzzle piece fit into the entire puzzle, because there's a lot more to it.

Kris Hampton 36:44

Yeah. Is there anyone that you wouldn't have stretching?

Paul Corsaro 36:50

Um, maybe.

Kris Hampton 36:51

What cases?

Paul Corsaro 36:52

People get pain in larger ranges of motion. Probably stay out of that. If folks tend to be on the more flexible side of things, I'm not sure that would be the... I don't think they...I don't want to say they shouldn't stretch, but maybe their time could be better spent elsewhere.

Kris Hampton 37:11

Yeah.

Paul Corsaro 37:13

But I don't know. It's hard to....it goes back to the blanket statement thing, right? We can't just

Kris Hampton 37:17

Right.

Paul Corsaro 37:17

Yeah, I don't... I don't really think there's any people who shouldn't be stretching. I don't think everyone should be stretching. You really just got to go with what you feel like you need and if it feels good and if you have the time to do it.

Kris Hampton 37:30

Yep, good advice.

Paul Corsaro 37:31

I like sitting on that fence. Can you tell?

Kris Hampton 37:34

Well, I mean, that's what a lot of this is, honestly, is sitting on the fence, you know, and, and doing it on a case by case basis. Everybody wants a magic pill and just a blanket way to improve, but that's not really how it goes.

Paul Corsaro 37:49

No.

Kris Hampton 37:50

Even with thousands and thousands of studies looking at it. Yep. You know, sometimes it just gets more confusing.

Paul Corsaro 37:56

We're still trying to figure shit out.

Kris Hampton 37:58

Yeah. All right. You can find both Paul and I all over the internets by following the links in your show notes. And you can find Paul at his gym Crux Conditioning in lovely Chattanooga, Tennessee. At the time you're hearing this episode, it's probably getting really nice in Chattanooga. So if you're out there, hit Paul up at Crux Conditioning. If you have questions, comments, or papers you'd like for us to take a look at hit us up at community.powercompanyclimbing.com. Don't forget to subscribe to the show. Leave us a review and please tell all of your friends who spend their warmup time telling you that you should stop doing any stretching in your warm up that you have the perfect podcast for them. We'll see you next week when we discuss flexibility specific to climbing and whether or not your poor high stepping ability is what's holding you back from those bigger numbers.

Paul Corsaro 38:46

See y'all later.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 38:48

It's done.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 38:49

You keep saying that and it's bullshit every time. Always. You know what? I'm done. Okay, you and I, we're done.

Kris Hampton 39:00

Breaking Beta is brought to you by Power Company Climbing and Crux Conditioning and is a proud member of the Plug Tone Audio Collective. For transcripts, citations and more visit, powercompanyclimbing.com/breaking beta.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 39:14

Let's not get lost in the who, what and whens. The point is we did our due diligence.

Kris Hampton 39:20

Our music, including our theme song "Tumbleweed", is from legendary South Dakota band Rifflord.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 39:26

This is it. This is how it ends.

Kris and Paul dig into a paper that presents and then tests a method for measuring movement skills in sport climbing.