Climb Better: How to Bulletproof Your Technique

"The close games are usually lost, rather than won."

What legendary basketball coach John Wooden meant when he said this, is that a mistake by the opponent, however subtle, is most often what makes the difference between winning and losing. Climbing isn't much different. When you fall just short of the chains, it's not an indication that you need to do something spectacular, but a reminder that somewhere below your efficiency dropped off. Your footwork or tension deteriorated. Your decision making slowed. SOMETHING, no matter how small, went wrong, and caused you to come up just short.

It's no secret that skills deteriorate with fatigue, particularly a complicated, high skill sport like climbing.

There isn't much we can do about that. We can, however, slow the rate at which those skills deteriorate. Essentially, you're already doing this through the projecting process. You realize that you fell because you lost tension and your butt sagged away on the big move. Next go, you focus on the tension, stick the move, and fall higher due to a sloppy foot placement. On the next attempt, you'll be more precise. Little by little, you're bulletproofing those moves.

Why not fast-track that bulletproofing in the gym? It's an important part of every route and boulder you do. Whether you're pumped or powered down, you need to know how to keep it together for those final moves to the summit.

I know, I know. The gym is for getting stronger, brah. Frankly, it doesn't matter in the slightest how long you can hold a front lever if you have to throw to every hold because you forgot how to create tension when your super strong core got a little tired. You'll fall just like the weaker people. Might as well learn to USE that strength.

Campus Punks

For these drills you'll need a campus board with feet and a nearby bouldering wall. If you don't have a campus board, you could easily get creative with a hangboard by doing repeaters or using the aerobic endurance hangs that Blake outlined in his recent post about training in a crowded climbing gym. You'll also need a brain and the ability to use it. I’m going to assume that if you’re reading this blog that you’ve met that requirement.

Campus Punks is a combination of a systematic physical fatiguing and a mindfulness/awareness drill. Here's how it goes:

Ladder on the campus board in a specific way.

Complete a specific boulder problem.

Rest. Repeat.

Take note of what deteriorates as you fatigue, and take steps to change that.

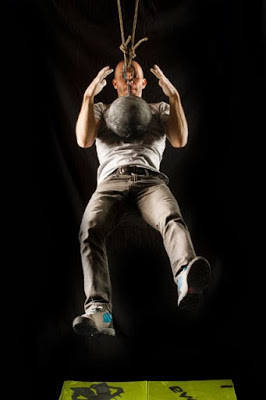

Aerobic Campus Punks

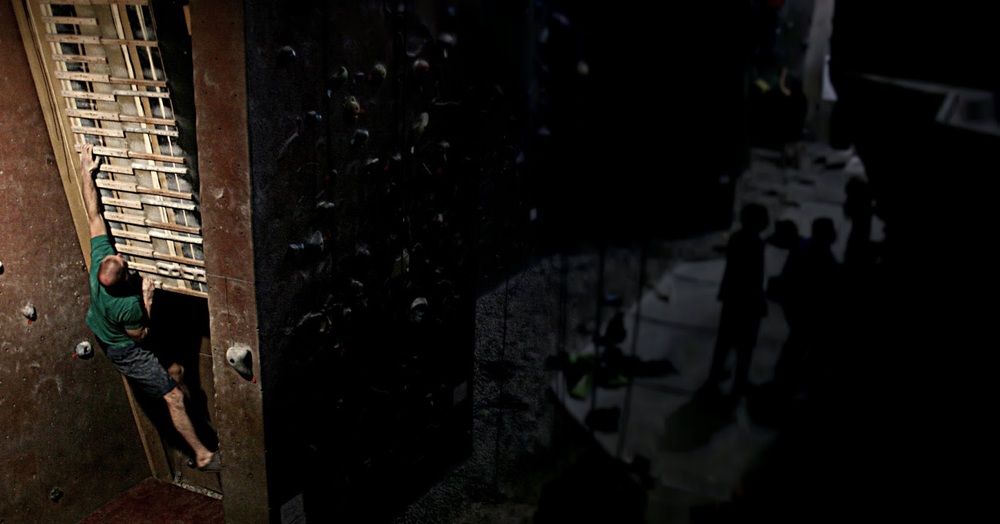

Anaerobic Campus Punks

Simple, right? Steps 1-3 will make you stronger, more resilient. You’ll be able to spend more time on the wall without fatigue. The real value comes in step 4, assuming you’re honest with yourself about your failures. This is where having the brain and the ability to engage it comes in.

First, let’s talk about steps 1-3. You’ll see in the above videos that we have two variations on the campus board. We do this because different types of fatigue will cause you to react in different ways, and we want to be ready for whatever the route or boulder throws at us. In these examples, the protocols are leaning toward Aerobic and Anaerobic.

Aerobic Campus Punks

In the first video, you’re doing a simple rung to rung ladder. We’re looking for forearm fatigue here. Pump. By using the campus board for this you can manage the time on the board so that you’re reaching just the level of fatigue that makes focusing on hard moves difficult. We like to find the time that just pushes you into that zone, and start there (usually somewhere around 50-70% of your max time laddering on the board, depending on your experience). Add time and/or more rounds as you improve. A good place to start is with 3-5 rounds of 2-5 minutes on the campus board, each round of which is followed by a moderately difficult boulder and rest that is about the same amount of time spent on the campus board (not counting the boulder).

Anaerobic Campus Punks

In video two, we’re doing bigger more powerful moves. I like to have a specific sequence of big moves and hops that I do each round, though it’s also completely valid to just go 1-4-1-4-1-etc. Regardless of the sequence, you’re looking for fatigue more in the big pulling muscles rather than simply a forearm pump. For this version, rather than stay on the board longer, we prefer to cap the time at 30 seconds and come up with a harder sequence or use smaller rungs to add load. A good place to start is with 3-5 rounds of 30 seconds on the campus board, each round of which is followed by a moderately difficult boulder and rest that is double the amount of time spent working (including the boulder problem).

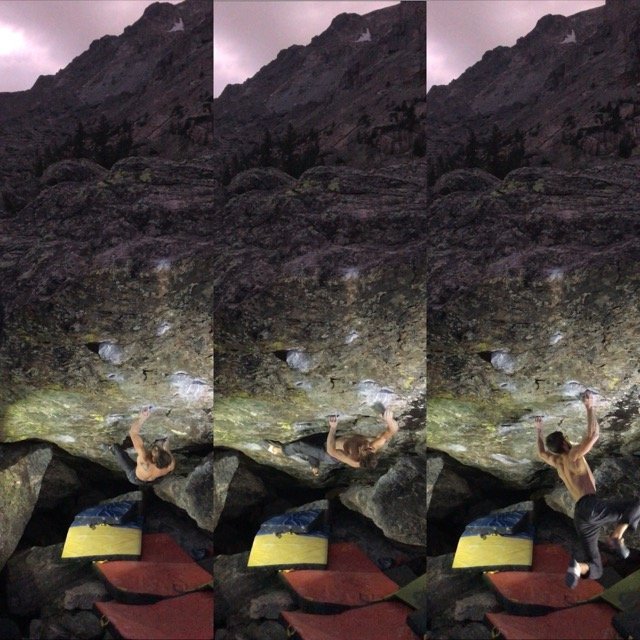

For both versions (or many of the other variations that can be created), you can always increase the intensity by doing a more difficult finishing boulder. I’d recommend holding off on that until you find that only an extreme amount of fatigue is sufficient to break down your confidence or movement on the boulder. You can also add a starting boulder, or combine different elements to create a more goal specific protocol. The below video demonstrates a variation for a very specific route. Once you understand the basic principles, you can be as creative as you’d like.

The benefits of using the campus board for this work should be obvious. First, you’re saving skin by using wood rungs rather than repeatedly pulling on plastic holds that wreck your skin in the same spot over and over. You’re also doing something that is much more controlled and repeatable over several training cycles. If your endurance circuit gets taken down between training cycles, how can you know exactly how your new one stacks up to the old one? This is also a nice way to work on endurance in a commercial gym that otherwise is too busy for you to be effective.

Now let’s take a look at the real money - Step #4. Did you fail simply because you didn’t have enough endurance? Doubtful. It’s more likely that you allowed doubts to creep in and take over. Or you forgot about placing your feet carefully as soon as fatigue in your hands reached a certain level. Or you felt tired so you lunged at a hold you needed to approach in a more controlled way.

Your skills failed - not your endurance.

Be honest about this, and make mental notes each attempt to focus on those small errors. Keep track of any “mistakes” in a journal (our Process Journal is built for this type of entry). Look back every few weeks, and pay specific attention to the small errors that keep popping up session after session.

Over time, many of the “fixes” you implement will become second nature, and you’ll find that they don’t show up as often. This makes for less time spent falling off the crux of your boulder project or that mega cave route due to a lapse in focus or technique. Fewer mistakes means faster sends. Faster sends equals more new rock climbs.

Now you’re winning the close games.

Kris and Nate discuss their favorite protocols, both that they use themselves and in programming for their clients.