The Once and Future Sport Climber: Part One

If you haven’t noticed the trend yet, most of my posts are really just open letters to myself in the form of hindsight. Hopefully, I’ll make the move to foresight someday, but for now this is what we’re working with.

Today's message will be the first of a series directed towards the Nathan of the past five years who was solely focused on bouldering and tiny sport climbs. It’s been a wonderful pump-free five years, but that time has come to an end.

As I switch back to sport climbing as my primary focus, I feel like this is a good time to reflect on and share some lessons I’ve learned over the past few years and talk on some things I’m having to relearn.

Background

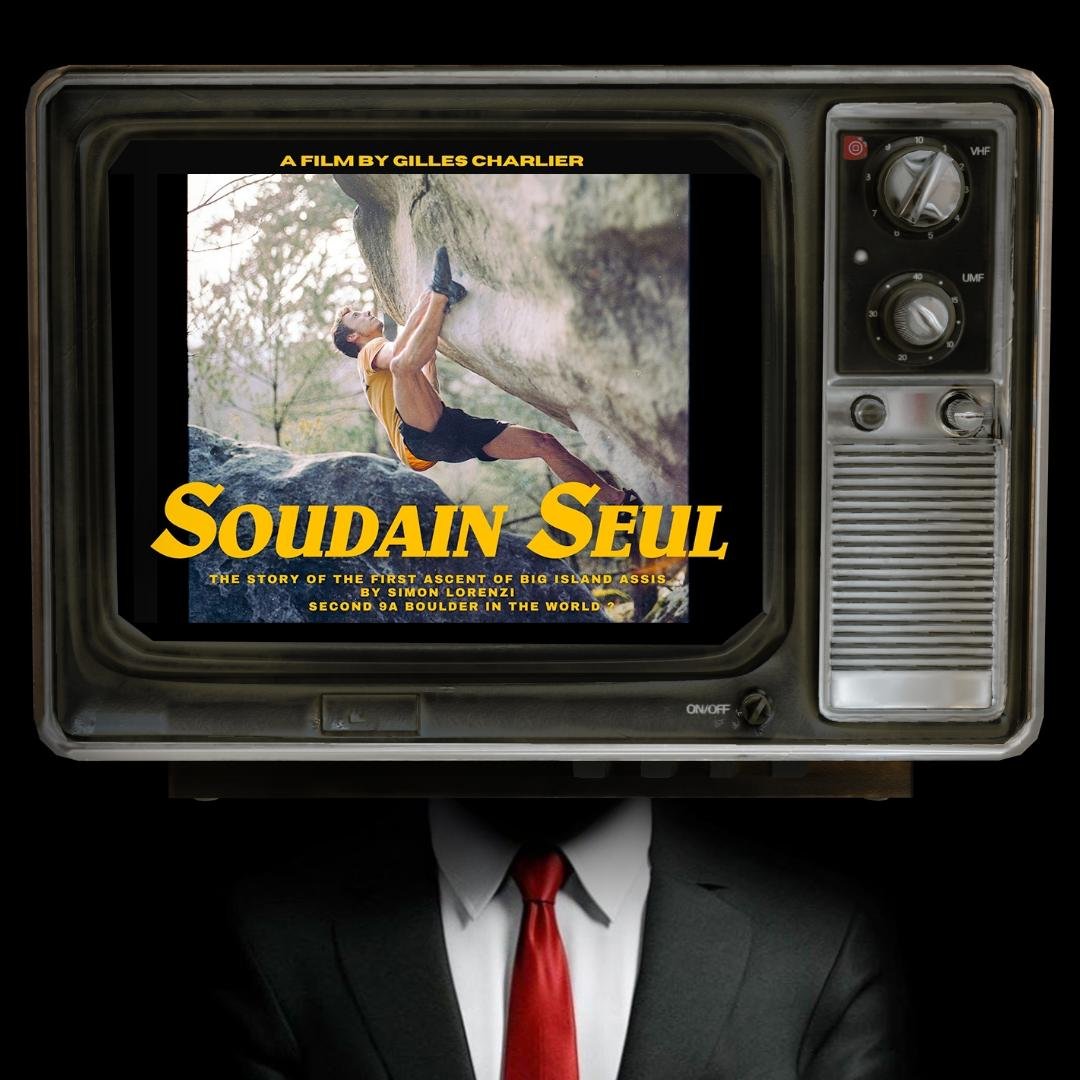

This was my longest break from sport climbing since I switched from being only a boulderer in 2006 (I would normally spend half or more of the year roping up). My last season of sport climbing (2013) was spent climbing bigger endurance routes like Omaha Beach (14a) and Transworld Depravity (14a). At the time I was fit enough that I nearly sent both 120ft routes in the same day *looks off to the horizon reminiscently*.

Omaha Beach (14a), RRG

After that season I felt that I needed to get stronger if I wanted to make the jump to harder routes and solidify myself at the 14- range. I changed my primary focus to fingery boulders since that’s what I believed was holding me back.

While I had good intentions initially, this post wouldn’t be happening if I had nailed the execution.

I lost sight of why I decided to put so much focus into bouldering and spent the next few years completely ignoring sport climbing.

2014

First year away from sport climbing. My residual fitness stuck around enough that I could still go out and be in good enough route shape to climb well without any endurance work. Sport climbed around ten days this year. I climbed a 13d second go, so I felt like I was doing something right. Focused heavily on crimp boulders, and the year culminated with a flash of the very crimpy Fingerhut (V10) in Joe’s Valley. Over the course of this year, using small holds went from being my biggest weakness to one of my dominant strengths.

Takeaway: Overall, I feel like this year was a big success in respect to making progress towards my long-term goals. My training was simple, when I climbed outside I allowed myself drop a few grades to focus on my goal/weakness (crimping), and I had great consistency throughout the year. Most importantly, I kept the goal the goal. If I could make any changes, it would be to get a few more sport days in and to have switched back to sport climbing after this year was over. I had met the goals I set out to achieve, and any time I put into bouldering after this year was for bouldering’s sake and not for my initial purpose of improving for sport climbing. However, it’s hard to stop and change directions when things are going great.

2015

I had a lot of momentum with bouldering success so I decided to see how far I could take it. By September, I had accomplished my year goal of sending ten v11’s. That winter I developed severe elbow issues that kept me from climbing for two months. Momentum came to a halt.

Historical records show that I only tied in once all year. It’s fair to say that this was the point at which I stopped keeping the goal the goal.

Takeaway: Don’t get greedy. While I enjoyed the bouldering that I did, it would have been easy to start working sport climbing back into the mix, especially after I hit my year goal. It probably would have kept the elbow issue from popping up as well.

Photos of nine of the ten 2015 goal boulders:

Top Row L to R: Western Gold (Laurel Snow), Gross Roof (Cumberland), Le Chninkle (Hueco)

2nd Row: Diaphanous Sea (Hueco), The Rhino (Hueco), Rogered in the Shower (Hueco)

3rd Row: Running Scared (RMNP), Golden Rows of Flows (RMNP), Hi-Fi (RMNP)

2016/2017

I had several large life changes and allowed my process to snowball into a lack of focus and a very distracted approach. I did a lot of bouldering and pretending not to be as terribly out of sport shape as I was. When I did go climbing, I hid behind short or bouldery sport climbs. This was beneficial since this had historically been the hardest style of sport climbing for me. I also realized that if I could sprint fast enough and use advanced resting tactics then I didn’t need much fitness to climb “hard”.

After a summer of only using body-weight training and campus punks (I was limited to only having consistent access to a campus board to train with), I was able to use that fitness along with a very tactical approach to have my best sport season ever by climbing two new 14a’s and a 13d that had felt impossible years before when I was at the top of my sport shape.

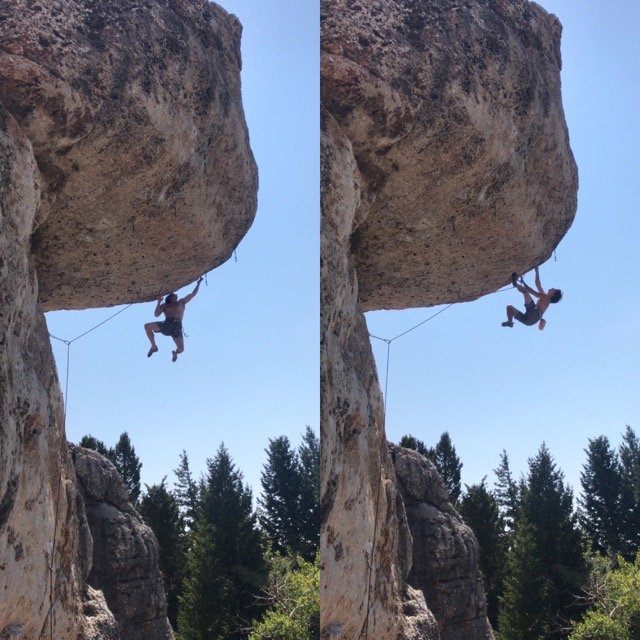

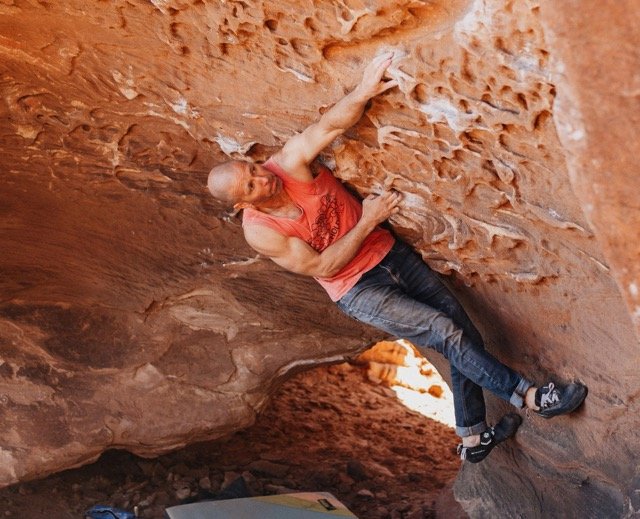

Dru Mack climbing Zookeeper (14a) in the Red River Gorge

Takeaway: Tactics, confidence, and a little bit of specific fitness can be leveraged heavily in sport climbing. It was sending these routes in such “terrible” shape that made me realize that I needed to stop letting myself be so distracted and return back to full-focused sport climbing. I also improved at climbing on powerful sport routes which was something that I had avoided earlier in my climbing career.

2018

Back to sport climbs where I can’t hide behind sprinting, kneebars, and handjams. Does pump ever go away? Asking for a friend.

Things I’ve learned so far or have had to learn again

It’s hard to keep your eye on the big picture when you train yourself

I know my climbing and my body better than anyone else so it makes sense that I should know what’s best for improving my climbing. Many plans start with great intentions but fall apart when we decide to make a few tweaks and “improvements” to them. It’s hard to always follow fundamental rules and make unbiased training decisions when you are the only one holding yourself accountable.

To quote Dan John-

“If you’re training yourself, you’ll tend to know everything you decide to do. You’ll always push yourself exactly as hard as you feel like pushing yourself. You won’t have any gaps in your training because you have no idea what you’re lacking. Finally, you’ll be able to progress and regress easily in your system since your single follower—you—will know what you want, even if it isn’t something you need to do. I hope I painted a picture of mediocrity here.”

Applying This

Following motivation can be wonderful, but it is far from unbiased. Occasionally checking in with a friend or coach to make sure you are moving in the right direction is invaluable. The more you know about training, the easier it is to justify ANYTHING you do. Find someone to help keep you on the path. An hour-long conversation with someone who can be honest with you can save you years of spinning circles.

Route Endurance comes back really fast...

…when you step away from sport climbing for 4-5 months, less so when you take off 4-5 years. My best hunch for why this happens is because aerobic endurance has very long lasting residual training effects. Which is to say that once you’ve invested the time to develop it, it does a good job of sticking around. To add to that, since bouldering continues to use the aerobic (oxidative) energy system, it is much slower to detrain than if you stopped climbing all together.

Applying This

Taking a winter off to focus on bouldering = not a huge deal

Only bouldering for half a decade = severely out of shape

Sport Climbing is Much Harder Mentally Than Bouldering

I somehow managed to block out my memory of how mentally exhausting it is to try hard multiple times a day while sport climbing.

With bouldering, it’s all over in a few seconds. You get focused, pull on, try hard, and execute. If you fall, you just have to wait a few minutes and then you can try again.

In sport climbing, sometimes it takes 20 minutes of strenuous climbing and resting before you get your chance to try hard, and if you fall you might have to rest an hour or longer before you can give it another worthwhile go. Depending on the route’s style and its orientation to the sun, you might only get one or two quality efforts in a day.

Applying This

Plan ahead for this. Make a day plan before getting to the crag as well as small goals for each effort to help break the route down to more bite-size and less intimidating pieces. If you and your partner have the type of relationship where you can hold each other accountable for sticking to the day’s plan, use that to your advantage. It’s easy to talk yourself out of doing the hard work once you’re tired. Having a climbing partner who can help you stay accountable is invaluable.

Build a Route Circuit

I took this one for granted while climbing in the Red. I had done so many of the routes over years of being there that it was easy for me to do laps at the end of the day after I was done with my primary objective.

At most of the crags I was climbing at I would have a 5.13 that I could use to finish my warm up and then a few that I could lap after I was done trying my project for the day. Since I was already familiar with so many of the routes, it was easy to get some extra volume and not lose fitness late in the season when I would be focusing most of my time on only one or two routes.

I think this is one of the most underutilized opportunities that sport climbers have access to.

The more time I spend climbing in other areas, the more obvious it is how much of a difference it makes to have a few dialed-in climbs in the line up. When the day is nearly over and I’m mentally cashed out from trying hard all day it’s much easier to run laps on a moderately difficult route that I already know well rather than having to venture up something entirely new.

To me, one of the most important physical attributes for a sport climber to cultivate is the ability to give multiple high-quality efforts in a day. My method of choice for developing this type of fitness is the inclusion of “circuit routes” at the end of the day after I’m done trying my projects.

Applying This

When I go to a new wall or area and I plan on being there for more than just a few days I need find a good moderate route for circuiting. Things to look for in this would be:

Skin Friendly- this should be a supplement to your climbing. If you have to rest for your skin because of this, then it’s not doing its job.

Specific Style- If I want to maintain fitness for short punchy routes, then I need to find a short punchy route. If I want something to keep me sharp at hard face crimping, then I need to dial in a technically challenging face climb. This route should either fill the gap that you aren’t getting from your project or it should be used to build more specific fitness for the route you’re currently trying. Grade is less important than style for this. Depending on my goal, I might get more value out of a steep and continuous 5.12c than a one move “circus trick” 13b.

Easy to Access- if you have to walk a half mile down the wall from your project or drive to another sector to get to the route then you won’t be as likely to climb on it when you’re already mentally drained from trying your project.

A 2-4 star route- this is heavily dependent on how trafficked your crag is, but if you pick a 5 star route that always has a long line on it, then it might not feel worth waiting around for.

Fun!- If you’re going to do something a lot of times, you should enjoy it.

BONUS: If you can use a circuit route to set yourself up for success with a later project then you’re killing two birds with one stone. An example of this would be either circuiting the bottom of a route that has a high crux, circuiting part of a link up, or circuiting a route that has a hard extension that you want to do in the future. You’re getting fitter and you’re getting free muscle memory for a future project.

Sprinting Can Carry you Pretty Far

Tactically, this is probably the best lesson I gained from getting so far out of sport shape.

Last year I spent a month training specifically for a 25-move route that I knew would take me just over 60 seconds to climb. Training went well and I did the route with plenty of autumn weather left over. The problem was that I was now fit for something very specific and there weren’t any other climbs like that around. What I soon realized was that if I could sprint between sit down rests, handjams, or kneebars in around a minute, then I could still climb bigger endurance routes. While this left me somewhat limited, I was able to squeak out two more good sends that season, Lord Voldemort (14a) in the New, and Super Charger (13d) in the Red.

Applying This

Specific fitness for routes can be developed with surprising success without having a base of general endurance to support it. However, without a broad fitness base to work off of, the number of quality efforts that you can give in a day/weekend drops dramatically.

Build the base, develop the specific fitness that’s needed, and remember how to climb like an out of shape slob.

My next post will come out around New Years and it will be a summary of my approach from this last year as I transitioned back to sport climbing and will include the things that both went well and poorly and how I plan on improving upon that this next year.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.