Steven Jeffery | Climbing in the Disinformation Age

Back in September, at the 8th annual Joe’s Valley Festival, Kris sat down to talk to local legend and longtime crusher Steven Jeffery, about how climbing has evolved since he first came onto the scene. They reflect on how today’s online resources like digital guidebooks and social media have impacted climbing.

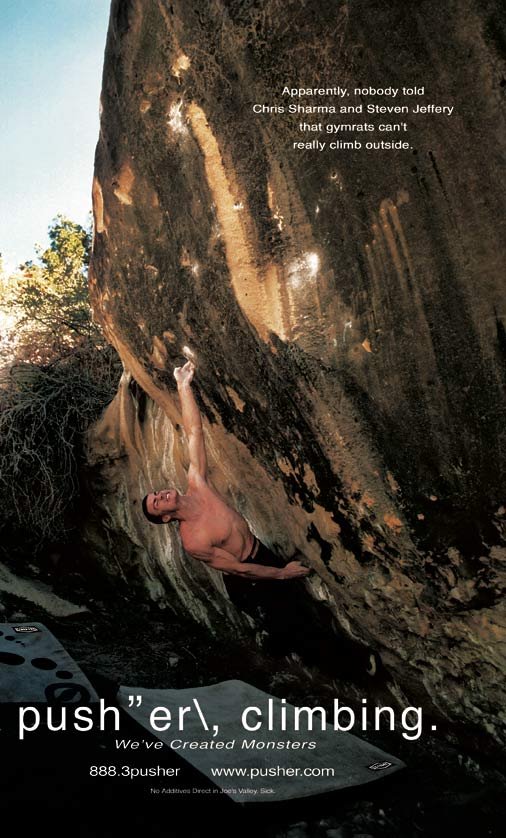

A young Steven climbing No Additives Direct in Joe’s Valley for an early Pusher advertisement. | Photo: Boone Speed

Steven’s contributions to Joe’s Valley reach far beyond his long list of FA’s. His work as an advocate and liaison between the local and climbing communities in the area show his commitment to ensuring sustainable access for future generations.

Steven and other volunteers doing trail maintenance during Joe’s Valley Festival. | Photo: Patrick Bodnar

DISCUSSED IN THIS EPISODE:

Steven talks about bouldering in a presentation to the Emery County Business Chamber. | Photo: etvnews.com

How Steven started climbing and development in Utah evolved.

The motivations behind a young Steven learning to “flip the switch” – whether in comps or outdoors.

The impact that a booming indoor climbing industry has had on outdoor climbing.

Steven’s thoughts on the recent chipping of classic climbs in Little Cottonwood Canyon and Joe’s Valley.

Why Steven chose to release his new guidebook for Joe’s Valley through the KAYA app.

FULL EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Kris Hampton 00:00

The Power Company Podcast is supported by our Patrons. They keep this thing sponsor-free, and in return, they get two bonus episodes every month. For as little as $3 per month, you can, too. patreon.com/powercompanypodcast or click the link right there in your pocket supercomputer. Thanks.

Steven Jeffery 00:29

Wow, how did this boulder problem come about? Well, a lot of hard work in building a trail, gaining access. None of that's shown. We're not getting enough information that's correct.

Kris Hampton 00:57

What's up, everybody? I'm your host, Kris Hampton. Welcome to the Power Company Podcast brought to you by powercompanyclimbing.com. I am here at home in Lander Wyoming, stuck deep into a training cycle and being a new dad for the second time and hoping that most of you got outside somewhere for the Thanksgiving break and that the send conditions were perfect. Whether you executed or not? I have nothing to do with that. That's entirely up to you. Either way though, I hope you learned some things. Before we jump into today's episode, I have to let you know that we're having a giant sale for the month of December. Our Crag Kits and Boulder Bags are at their lowest prices ever, alongside Finger Files, Finger Care Kits, apparel, hats, books, and more. We don't do this very often. So get in there before things are gone. And if you're buying something as a gift, do it ASAP. Because the post office during the Christmas season is slower than your everyday average offwidth climber. And that's pretty damn slow. A couple of months ago at the Joe's Valley Festival, I sat down at the Emery County Rec Center and the rodeo grounds at the park there with Steven Jeffery, a climber who has – whether you know it or not – had a hand in the way most of us currently experience climbing, several facets of it. While he's mostly known today as the unofficial mayor of Joe's Valley, what some of you newer climbers may not realize just yet is that Steven was instrumental in the role of route setting in indoor climbing, he was on the podium at early climbing competitions, he helped usher in the eras of both bouldering and big macro gym holds. And when I hear the sound of a sloper being slapped just perfectly, which actually is one of my favorite sounds in the world, with that snappy thwack of aggression and belief and rebellion, that is the sound of Steven Jeffery. Let's get into it.

Kris Hampton 03:23

So these little grips that you're pulling out now, that one came from Todd Skinner's old woody.

Steven Jeffery 03:29

Oh, man. I actually climbed on that. 25 years ago.

Kris Hampton 03:33

Directly off of that woody.

Steven Jeffery 03:35

Nice. Yeah, my first trip to Lander, Iris, ran into those guys and took us, we went checked out his wall and climbed on it. That's awesome.

Kris Hampton 03:47

You may have grabbed that hold 25 years ago.

Steven Jeffery 03:50

I probably did.

Kris Hampton 03:53

And then there's another little granite chunk in there. That came off of – theoretically, I have no proof – but I believe it came off of Dave Hume's home wall.

Steven Jeffery 04:06

Really?

Kris Hampton 04:07

Yeah.

Steven Jeffery 04:08

Haven't talked to that guy in a long time.

Kris Hampton 04:10

No, I haven't either. And I, the last time I talked to him, I sent him a photo of a bunch of these that I had been told came off of his wall. And he was like, "Yeah, they could have. I can't say for sure, but they definitely could have come off my wall." So...

Steven Jeffery 04:25

That's cool, man.

Kris Hampton 04:26

I know you competed with that guy way back.

Steven Jeffery 04:29

Yeah, he pulverized us all.

Kris Hampton 04:33

He was a quiet little monster, man.

Steven Jeffery 04:36

Random kid that – no offense – looked kind of goofy to us. And taught us a lesson that, watch out for the goofy kids.

Kris Hampton 04:46

That's rock climbing now.

Steven Jeffery 04:47

Yeah, it was like holy cow. He climbed so well. It wasn't that he was strong, it was just he climbed so well, right? So it was super awesome because it was like, you can't underestimate anyone at that point in climbing. It was so fringe and everything was so new and everyone was going at it. It was like, the weirdest-looking character would show up. You'd be like, "Whatever, they're not a climber." And next thing you know, it's like, oh, boy, like you're in trouble because you underestimated something pretty hard.

Kris Hampton 05:15

Yeah, totally. I have this great memory of Dave from a comp in, at Climb Time in Cincinnati. And he, he had already won by a mile. But the final boulder he, he didn't do it. And he was so excited to keep trying it. Like as soon as he would drop off, he would just run back to the start and try it again. And try it again. And try it again. And time had ran out long before. But he just was so excited to climb on this boulder, you know, and that's stuck with me all these years, is the excitement that kid brought.

Steven Jeffery 05:50

It was because he'd never, it wasn't about the competition against others for him. It was about, he's a purist climber, in a way. It was always about him and climbing what was in front of him. It wasn't about, he didn't care if he won. That was, in his mind, he lost – he didn't do it, right? So in his mind, he was probably still thinking, "Well, I didn't do it. So how did I win?" You know? That's like that purist climber thing that David Hume's had forever. It wasn't like, "Oh, dude. Well, I won. I'm just gonna stop." For sure, in his mind, "No, I didn't do, I didn't do that climb. So how can I say I won?"

Kris Hampton 06:29

Yeah, I think that's a, an ethic that was kind of passed down through, you know, through the way people learned to climb back then. Like the gyms were really early. And I, you know, I want to establish some of your history before we get too deep into this thing. You started in like late 80s, right?

Steven Jeffery 06:47

89-ish. Yeah.

Kris Hampton 06:49

And what was the, I mean there, there couldn't have been much of a gym scene, so did you learn outdoors? What did that look like?

Steven Jeffery 06:57

Yeah, climbing gyms weren't, there wasn't a gym scene. It was all mentorships and outdoors. So our climbing started as, my older brothers we were skiers, we wanted to go skiing. And ski the chute that you happen to have to rappel into. So we went and found someone that knows how to kind of rappel. And so we literally wrapped a rope around a water aquaduct in a canyon and rappel. And then had to walk all the way back around and it was like, "Well, this walking around kind of sucks. Can we just like climb back up and fully just rig it?" Guess you tie a knot like this. This eight ring, this eight ring rappel device will, does this. So if you do it backwards, it should be safe. And just go for it. Like fully just grinding a rope over a wood aquaduct. Like there's no anchor. And like, "Oh, this is kind of cool. Maybe we should start climbing." And then that's, it was like, "Oh, well. How do you do this?" Well, everyone back in that day would talk about the Rock Kraft book. And oh, it was like, it taught you anchors. But, and fortunately, we were lucky that a gear shop in Salt Lake existed called "IME". And the guys at IME are definitely, they're friends for lifetimes, you know? They still tell stories of 10-year-old me and stuff like that, which sometimes is embarrassing, but it's what it is. And then a co-op formed next door. And that co-op formed "The Body Shop". And Dave Bell was an inspiration of: indoor climbing could be something cool too. And so we had this garage, an old car shop, The Body Shop...

Kris Hampton 08:38

That's cool.

Steven Jeffery 08:38

And then we climbed in this old garage as a co-op thing. And it was a place I could access, because I couldn't drive a car, I was a kid. But you know, the local UTA bus would get me there. And so I climbed in there on plastic. So I'm kind of like the first plastic gym rat that's ever existed.

Kris Hampton 08:58

Oh, wow, yeah.

Steven Jeffery 08:59

Because that was where more of my climbing came, and then the mentorship to be outside was there. Because there were so few climbers. And there was plenty of mentors.

Kris Hampton 09:09

And those guys just took you under their wing.

Steven Jeffery 09:12

Right. Because some of those guys, I think, got a little bit bent that I could do stuff in plastic they couldn't. And so they wanted to make sure that this kid was in-check and will come to the real world. And it, it did, it did put you in-check. It was like, "Whoa, okay, this is really scary. This is really hard. And this is movements and stuff I don't understand." And these guys just kind of wanted to make sure that they weren't getting beat down by some little kid on plastic. Yeah, so it was kind of like this, "We'll take him out for entertainment. And we'll see how it goes."

Kris Hampton 09:50

Was, was sport climbing a thing in Salt Lake at the time? Like was that when sport climbing was sort of really blowing up?

Steven Jeffery 09:58

So sport climbing did start blowing up early 90s, right after the whole Smith Rocks begins and stuff like that. We started out trad climbing. And I remember thinking about sport climbing for the first time going, "Wait, what is it? It's just bolted routes? And they're steep?" And in my head I'm imagining all the friction slabs of Little Cottonwood. 40 foot pitches with one, one bolt; 60 foot pitches with two. And I was like, sport climbing sounds like the most dangerous, scary thing to an 11-year-old kid ever. I was just like, "I can't imagine this." And so we climbed trad routes. It was fun. You just keep plugging in stoppers and going. And then, we were climbing 5.9, it was like, "Yeah, we're gonna one day climb 5.10." And then we decided to go check out the sport climbing in the other canyon. And when we got there, it was total shock of like, "Wow, this is very unscary." Immediately went from 5.9 trad to 5.11 sport routes in like a weekend. And it was like, "Wow, this sport climbing is different. It's safer in a way." You felt so safe with it.

Kris Hampton 11:07

I'm curious, you're like, one of the things that struck me about you when I first saw a video of you climbing, way back, is that you kind of have this quiet demeanor. Until you pull on. And then you like become this embodiment of aggression when you're climbing. Where did that develop? Was it, was it through the mentorship? Or was it something that you just brought on your own?

Steven Jeffery 11:39

It's, I call it "flipping the switch". So coaching kids, so I coached Nathaniel Coleman for a while, and the coaching is not about the climbing part. It's about the mental and flipping the switch. And for me, when I was a kid, I was climbing around all these adults and I always felt like I had something to prove. Always. It was like, "I'm just this kid and I have something to prove." And so I learned to make every attempt count, every attempt mattered. Because it was, "Well, I want to burn off Boone Speed," right? This is the world's greatest climber at the time. And he's standing right behind me. And I want to burn him off. Because it was like, "I want to show off." And so you'd learn to take this seriousness in every attempt, which was really great, because it was like, "Oh, flip the switch, kill mode." But then my older brother was the one that kept me in line of, "Don't be a little shit," right? "You can't be, you can't say something's easy. That's offensive." And I was, I was always like, "Whatever. Well, it is easy." 30 years later, I feel bad for ever saying something was easy in climbing. But back then I was just this little wiry kid that could hang on to anything. And it was like, "Oh, well, that's easy." And he's like, "You can't say stuff like that." And so I learned to control both sides of, "Well, if I can't say it, I'll prove it." Right? So it was like turn around, climb the climb, and prove that it's easy in a way. Not, not to use your words. And that carried on to that footage you're talking about in comp climbing. You know, I wanted everyone to know, like, "Hey, this is a fun thing. Comp climbing is a little bit weird. We're competing, but that's actually my friend next to me that climb with. I don't want to think that we're trying to kill each other. We're actually all friends out here." And so I wanted to keep that atmosphere. But then when I turned around it was like, it's, it's kill mode. It's, this is the goal. This is what needs to be done. If I can get done in 30 seconds, that's great. And then I can just chill with everyone again, right?

Kris Hampton 13:51

Yeah, that set you up well for like the competition scene kind of coming into its own when you were right at the right age to be competing and right at the right, you know, level to be competing with, with Chris, with Nels and with... you know, you are on the podium with these guys at a lot of these comps. And it seems like that "flip the switch, kill mode" set you up really well.

Steven Jeffery 14:20

Yeah. And I learned that and also how I learned it is, believe it or not, I'm a chicken. And climbing is scary. And I didn't ever want to fall off anything. And so that focus really came from like, "Oh, man. Don't fall off, you know, this is scary." And I was genuinely scared in a lot of ways too. So that mode of "don't screw up" became even more focused because I was scared of... man, climbing is scary, right?

Kris Hampton 14:46

No doubt.

Steven Jeffery 14:47

And still scary as you grow older. And everyone will admit that taking the whipper or climbing that high problem, it takes a bit to get back to it, you know? People build back up to it and a lot of people don't hear that. So they just think they go for it. And so it's like, whoa. So that also was a part of, a product of me truly being scared of climbing.

Kris Hampton 15:10

Yeah. That's interesting. I'm glad you said that. Because I think a lot of people don't give that fear enough credit, you know? And it's the process of learning to feel the fear, recognize it, and then work your way through it. And it's just, you and I might work through it in a few seconds. And some a new climber might have to work through it over a series of days, or whatever.

Steven Jeffery 15:33

Right, right, for me, it's years.

Kris Hampton 15:35

Yeah, sometimes.

Steven Jeffery 15:36

I don't work through it quickly.

Kris Hampton 15:37

No, sometimes it's definitely like, oh, I need to bring a top rope out here, I need to, you know, have a bunch of friends to spot, I need, you know, whatever I can do to mitigate the danger so that I can lessen my fear and work through it.

Steven Jeffery 15:51

And then the danger, and then in the comp scene, too... So the old PCA days with all of our friends climbing, there was also a urgency of: these people came to watch us. And I would feel bad if we performed poorly. Me and Chris kind of shared this same feeling of that in these comps. It's like Sharma would show up and be like, "Oh, man, I don't feel very good." When we'd get these nervous feelings of, "These people came to watch us. Crap, we better not screw up," you know. And so that's what where all that switching comes from is like, I would feel really bad if someone drove all the way out here and I just stood on the ground because I couldn't do anything, you know.

Kris Hampton 16:34

Totally. At that same time that the PCA's were blowing up was kind of this first big bouldering boom. Was there any like pushback in the Salt Lake climbing community, for the bouldering boom kind of taking over from trad and sport climbing?

Steven Jeffery 16:56

So, back in those days in Salt Lake, there wasn't... like the climbing scene, everyone respected everyone, because everyone was a master at that craft, right? So there was always people you would see and you just be like, you knew what they did last weekend. You knew they did that R X trad route. You know they're not a boulderer. So that mutual respect between the different styles of climbing from trad, sport, to bouldering, was across the board. No one was in a hierarchy because those climbers at the time like Boone Speed's, the Mike Call's, and Dale Goddard, and those guys were climbing all the same too. They would boulder, they would trad climb, they'd sport climb, they'd do first ascents, and, and there was like this mixed – it wasn't a mixed review, but it was an even playing field. Each sport was, each activity in our sport was the same level. And at that time there was enough room for us all to grow, you know? The boulders were over there. The trad routes are in this canyon, the sport climbing is in this canyon. And there was enough room to go around. And the old old-schoolers, you know, like they, they thought it was kind of cool. You know, we had some old legends. Our Old Salt Lake City Mayor was a climber, Ted Wilson, and he established trad routes back in the late 60s, early 70s. Bold climber, became the Salt Lake City Mayor for a while, and he still saw it as like, "This is a cool evolution of the sport."

Kris Hampton 18:33

I had no idea. It was like highlighted for me, though. Like where I was, there was a bit of a division between boulderers, sport climbers, trad climbers, but then "Three Weeks & a Day" came out. And, and if anyone listening hasn't seen "Three Weeks & a Day", I don't know if it's available online anywhere.

Steven Jeffery 18:53

Dude, I tried to hunt it down like a week ago.

Kris Hampton 18:56

It's so good. Classic Mike Call film. I've got it on VHS still, I love it. But in that, they make the first trip, that anybody else ever saw, to Joe's Valley. They also, when their RV breaks down, they find some crack climbs out in back of the, the shop and they're just climbing these crack climbs, you know with gear. They brought gear with them on their trip. And then they go to try to climb these new 5.14 sport routes in Mexico.

Steven Jeffery 19:29

And that was what climbing was back then, it was climbing. It wasn't broken down into categories so much. We were climbers, going climbing. You'd go aid climbing and then next weekend you're out bouldering and it was like totally normal. It's like, "Oh yeah, I was doing some scary aid, terrified the crap out of me. Oh, now here I am bouldering on this boulder that's three feet off the ground and I'm scared for some reason." You know, it was just climbing.

Kris Hampton 19:54

How did you get involved in the like shaping route setting side of things?

Steven Jeffery 20:02

So I was probably 19 years old, so early 90s. The Wasatch Front Rock Gym begins and Rockreation in Salt Lake City. The first kind of bigger gyms opened pretty close together. And as someone that can't really drive a car, can't get anywhere, these gyms became places to go and naturally, you just want to, oh, you start putting holds on, you start, you start creating movement in climbing gyms. Because back then nothing was marked. It was just holds on walls and everyone just made up things and you just shared it.

Kris Hampton 20:40

It was just a building with a bunch of spray walls.

Steven Jeffery 20:42

Right. Yeah, it's funny because climbing gyms are coming full circle almost nowadays, like went all the way from route setting, now it's back to this, "Oh, the spray wall scenarios are really cool." And so that was just kind of how it was going. And then Dave Bell and Rob Gilbert out of Salt Lake start, well... climbing holds aren't, there's only these few holds, these holds we have here. And it's, it was kind of boring in a way. So Rob Gilbert and Dave Bell decide, "Let's start a hold company." And that's when Pusher began. When Pusher began, it was just as punk rock as it could get. You know, it was just literally, they were all kids at the time, everyone was kids, and they were just like, winging it. It was cool. So anyone could pick up a block of clay back then, and foam wasn't even shaped at the time, and make something and it was like, "Put it in a mold!" You know, it's just how it was. Anything was gonna be cool other than the current holds.

Kris Hampton 21:41

Yeah, I've always sort of equated like, I'm pretty sure Mike shaped the "Boss". Is that right?

Steven Jeffery 21:47

Mike Call and Marc Russo kind of worked on the Boss because they went on a Font trip.

Kris Hampton 21:52

Okay. And that was one of the first big, like, macro holds. And even though Mike shaped it, I've always sort of equated it with you. Because of the like aggressive, physical, slappy style that we saw you climbing with. And we saw, you know, Mike's footage of you, Boone's photos of you, and it all contributed to this like, really aggressive punk rock sort of ethic.

Steven Jeffery 22:20

Right, because believe it or not jumping around in climbing comps is new. For all you people seeing it now, that's new-ish. Climbing was a very controlled movement back in the day, it was about holding moves and doing moves. And then...

Kris Hampton 22:38

It was almost dainty.

Steven Jeffery 22:39

Yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah. It was like, oh. But then the PCA comp circuit comes around and it's this young, like, "let's make this rowdy." And then these big holds come around that there's nothing to hold on to. So jumping and slapping became the thing, because that was the only way we're going to hold on to these things. And so it became this rowdy visual that everyone's gotten of like, "How in the world, you know, did Chris jump to this thing and stick the side of it?" He didn't get on the hold, he didn't quite make it. And now he's holding on to nothing on the side of the hold. And then it's just turns into this chaos. And I think that's where that came from. And it's these images of, I mean, I have good fond memories of the Boss and winning comps because that damn thing was on the wall. I'd turn around and be like, "Oh, thank God, I can hang on to that, at least." All the other little things that I could barely see on the wall, the crimps, I was like, "Oh boy." But if I get there, I could just hang out. And everyone else was the opposite. They'd look up and be like, "Oh, no, there's the Boss. I'm dead." But me it was like, "Oh, thank God." I could shake out because I knew how well the hold suited me. And that was the style of climbing I really was after, and I liked, I liked the aspect of grabbing something that wasn't there and trying to use it versus digging my fingernails into something. Although, I did.

Kris Hampton 23:59

I'm curious too, like, I've talked to a lot of youth competitors, like in today's youth circuit, that's really super high pressure. And they're all like, "Oh, no. World Cups are a cakewalk in comparison to youth comps." You know, I'm curious if that pressure, or that like... was there any, did it get into your head competing with like Chris and Nels and Dave Hume? Was there any of that there?

Steven Jeffery 24:30

No, I didn't get like nervous or anything. I was honestly kind of maybe doing it to prove a point in a way that anyone can be here if they try hard, right? Because I came out of Salt Lake. My family wasn't well off in any way, but we weren't poor. It wasn't like we couldn't do things but you had to go and do it yourself. You had to go make things happen. You couldn't just be like, "Hey Mom, Dad," it was you had to do it. And I liked to, I used it to kind of prove a point. Like, I felt magazines and stuff would portray stories wrong, videos would portray ascents wrong. It's like a skate flick. You watch that person rip out a line on their skateboard and you're like, "Oh, man!" But that, that was like, attempt 70, you know. And I saw the attempt 70 to do that, but then everyone's only seen the number one attempt. And it kind of bugged me because it was, I felt like people were getting false, false, you know, realities of what was happening out there. And so I liked to go out there and be like, "Yeah, I worked 40 hours a week at the grocery store and beat them. And these guys are professional climbers, I guess?" you know. And I'm considered a professional climber too, but not really. And that's, I got in lots of binds as a professional climber, a sponsored climber, because I would, didn't mind calling them out, that, "Well, you just gave me a pair of shoes, you know. I can go work at McDonald's and buy a pair of shoes faster than calling, calling and begging you, you know. Like, why would I keep begging?" And so I, I never felt a pressure of it. It was more, for me, it was more I have to prove the point of anyone can be here, if you want to be here. I never worried about winning or losing. It's probably what kept me always on podiums, because it's like, "Whatever, I'm here."

Kris Hampton 26:26

Yeah, yeah. How did the like... back in the, back in those days, the gyms were like, you know, trade, trade a membership for setting.

Steven Jeffery 26:37

A lot of that.

Kris Hampton 26:37

You know, whoever comes in can just set whatever they want, you know. How did you start trending toward route setting more professionally, more, more as a career and for big comps?

Steven Jeffery 26:51

So obviously, you know, you're getting weaker, I guess, or comps are getting harder, and you need to do something, right? A lot of these guys just thought this would last forever. For some it lasted a little bit, more for one: Chris, is the one. You know, and so a lot of us realized quickly, like, "Oh, what are we going to do?" And so for me, it was like, "I need a job. And climbing has been my whole life and I love it. What am I going to do?" And so it was pretty like, "Oh, well, there's this evolution coming: climbing gyms." So you master movement out of fear because you don't want to fall off. So magically your a master of all climbing movement, magically, and then next thing you know, it's you can translate that onto this artificial wall. And then you can become this skillful route setter of movement, right? And I was, God, I was probably only 15 years old. Rockreation was hosting a qualifying round for a Snowbird comp up at Snowbird Cliff Lodge. And the finals round was happening at Cliff Lodge, and it snows. And they were in this panic mode. So they hurry and put the finals route in Rockreations gym. And they throw down in the finals. And Scott Franklin wins, the classic days of that. And I watched all that and I was like, "Wow," and then the climbing team was empty. There's no holds, no nothing. And I was sitting there, and everyone's burnt out from the mad chaos of trying to put up and I was like, "Well, I can put up routes." And I set these routes as a 15 year old kid, and people climbed them and they we're like, "Wow, this is really good route setting. And this is really fun." And I was like, "Oh, this is cool." And so I got into that route setting thing really young, luckily, by you trade a membership to route set. And then people started seeing and realizing, "Wow, this is... Wow, the climbing gym is really busy all of a sudden, and all these people are climbing these routes and they talk about them." And that's how it kind of transferred into that. But at that point, climbing gyms still weren't a big thing out there. It took a while longer.

Kris Hampton 29:03

When the gyms did start blowing up? Were you excited to move into that? Or were you a little nervous about the idea of it blowing up?

Steven Jeffery 29:13

I was hesitant for sure. So I was managing freight crews at grocery stores, working graveyards for like seven years, and then just climbing every day. And then a large gym brand was starting in Salt Lake. And it was Momentum. It was we're going to build this big huge climbing gym in this, you know, commercial real estate place. It was kind of like, "There's no way you're going to do this. Like sure, whatever." But as I'd drive from my home to American Fork, you'd drive right past where they're building it. And every weekend you're like, "Wow, it's a little bit, whoa, they cut the roof off. Well, oh, there's a whole..." and your kind of like, "Whoa, they're, they're doing this." And so I randomly was just like, well, I'll just stop in. You know, check it out. I was actually planning on leaving Utah at that time because I felt I'd climbed everything. And I was going to move with the grocery company because they're a massive company, I could go work anywhere, but I decided to go in and look. And I went in and looked, and randomly this guy, Big D, Demeter from Walltopia at the time, I knew him from random other things. And he's in this building, and he's like, "Whoa." We're like, "Wow, what are you doing...?" He showed me everything they were doing. And I was like, "Wow, this is amazing." And at that point, the gym was thinking about how they're gonna start selling memberships, what was their, what was their angle to convince people you need indoor climbing and outdoor climbing. And it just happened that me standing in the building really helped them out. Because people who were coming and peeking around were like, "What's Steven doing here? Does he work here? Like, is he going to be a part of this gym?" Because when we lost the Wasatch Front, it really, that gym, when that gym was lost, it really a lot of people were hit hard. They felt lost with their climbing gyms. They didn't know what to do, they never felt a home.

Kris Hampton 31:05

It's not like today where there's seven other gyms in town.

Steven Jeffery 31:08

Right. And so I, they asked me what my plans were. And I said these are my plans and they thought, Momentum thought they could change them. And they did. They changed that plan for me.

Kris Hampton 31:20

Cool. Well, fast forward. And you know, and maybe not even fast forwarding that much because you had Little Cottonwood there but, you're developing bouldering outside – do you see any parallels between the mindset of route setting and the mindset of developing?

Steven Jeffery 31:42

Right, yeah, you do. So I'd route set, climb in gyms, and I was like, "Man, these moves are cool. I want to find them outside." Because I can manufacture any type of route on plastic and in a gym. And this move's, "Oh, man, this move's sick!" and you want to go find it. And so finding boulder problems became a thing, right? It was like, "Oh, I gotta go find it." And so you want to do these first ascents. But then at that time too, first ascents were kind of king, you know? It was like, "Oh, you repeated that. Oh, you repeated so-and-so's. Yeah, you repeated, repeated. Yeah. But you did what?" It's like, "Oh, I did this new line." And so that kind of became cool to me, too, because it's is these lines possible? Just how many first ascentionists.... It's like, everyone, is it climbable? Is it not climbable?And the route setting helps with that, because your movement you're trying to create, you have to do that with the first ascent. It's like, you're looking at something that's relatively blank and granite, and it's like... And then, two days later, you're like, "Oh, crap, it's only V5." Right? It's this puzzling game that you learn, where people thought something was impossible and here you are, "Oh, it's not that bad, actually."

Kris Hampton 32:55

Yeah, I've heard several people talk about you like showing them some things that you've cleaned up and built landings for, and just handing it over and just being like, "Hey, you climb on this." You know, at what point do you think the "I have to get the first ascent" dissipated?

Steven Jeffery 33:18

Um, for me, it disappeared when I just realized it didn't matter. You know, like, the reason why I got the first ascent is I was the first one to find it, I was the first one that walked out here. Any, someone else could have done that. So the first ascent kind of disappeared for me because of that, it was like, "Well, you were just the first one out there." And what changed for me was is Adam Ondra actually changed that. Ondra was so competitive about beating records. "Well, how fast did that guy do it? How many tries did that take?" And to me, it was like, you know, he's actually right. There's only one aspect in climbing that matters, on any climb, anywhere: it's first try. We all only get one first try. And if you don't do it first try, it's over. So doesn't matter if it's a first ascent, 100 billionth ascent, it's first try. Because all of us get that. No one else can take it away or anything. It's... so when that came about to me it was like, "Oh, well, that's all that matters to me, too, in a way." A long time ago, it was like, "Oh, yeah, I can try a boulder problem 10,000 times and do it." Well, that's cool, but that person did it in four tries. It's like, "Whoa, it took me four days." And so that's when the first ascent lure disappeared for me because I would do a first ascent and be like, "Yeah, I just did this boulder problem, it took me five days," and I'd show it to my friend, he does it in four tries. I'm like, "Oh, man."

Kris Hampton 34:51

Yeah, I sort of have like, had the same evolution in my thinking where I used to really care about being the first to do a thing. And then I just realized that it's exactly the same challenge for me whether I was the first or the 150th, or the 10,000th. It doesn't really matter. It's still the same challenge.

Steven Jeffery 35:13

Same challenge, but what's impressive is is that person did it first try and you didn't.

Kris Hampton 35:18

How hard did I try?

Steven Jeffery 35:20

It doesn't matter if it's the V1 slab you fell off of or the V10 you flashed, it's like, first try. And so that's where that first ascent allure disappeared a little bit. And, you know, you get old. You know it's doable, because you've done things, but there's no way in hell you're doing it, so you might as well fix it up and let someone else do it. Because you know you're not doing that thing.

Kris Hampton 35:45

Totally. I find a lot of joy in like, cleaning things and, and making sure the landing is good, and then showing it to other people. Even if I haven't done the thing yet.

Steven Jeffery 35:57

Right. For me, I do that, too, it's... for me, it's changed, in a way, of the first ascent or an area's.... Since there's the masses we see nowadays, I'm starting to see it more as preserving what was there, in a lot of ways. I see it as this, yeah, I was the first one that found it – big deal. But I want it to kind of stay in this state...

Kris Hampton 36:23

Make it sustainable.

Steven Jeffery 36:24

And make it sustainable, because, you know, you find this amazing boulder problem, or you bolt this route, and you're just like, "Holy cow, I want it to stay in this state how I found it. So how do I, what can I do to preserve this state?" And that became really important to me. And that's how the whole Joe's Valley of everything came about for me, was seeing things change. And it was kind of painful to see the change.

Kris Hampton 36:50

Yeah, I think ,you know, that's a really interesting part of your story. Like you, you came in with this like punk rock, fuck the system, kind of attitude, you know?

Steven Jeffery 37:01

Maybe a little too much of a fuck everyone attitude.

Kris Hampton 37:05

Well, I, you mentioned that you started climbing around 1989, and I looked up some of the music that came out around '88/'89.

Steven Jeffery 37:15

Bad Religion was it.

Kris Hampton 37:16

Bad Religion had come out, NWA had come out, Ice-T released "Power", there were all these. Public Enemy released "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back." All these fuck the system attitudes were, were pervasive in like popular culture, at least for like, the young people who were looking for that. But then somehow you went from Bad Religion to "I'm going to join a trash cleanup in Orangeville, Utah."

Steven Jeffery 37:55

There's a few phases between there. I had a Katy Perry phase, you know.

Kris Hampton 38:00

There was no Katy Perry in there.

Steven Jeffery 38:01

There was phases, there was phases I went through to get through there, right? You know, it was, it wasn't a night and day switch. But it was drastic for my 30 years climbing, you know. It was a two year period of just like, "Wait a minute. This, these things need to change." And that big wave change came with the outdoor, outdoor climbing in the indoor climbing industry. I was in the indoor industry heavy for many years and watching how that industry was just exploding. And eventually, these people are going to go where we all want to go, you know, so it was this very concerning thing that I saw building. Just like being a scared climber, you're always four or five moves ahead, because there better be a jug there to clip that damn draw, because I'm so scared. So I, you develop this always looking ahead of what's coming. And seeing that in the gym industry was quite scary. Because I know how much fun rock climbing is outside. We all do. But this new breed of climber learning from these gyms don't yet. And when they do, what in the world are we going to do? What's going to happen? And so I took, in the 30 years climbing, there was a time where I took a good serious four years that I didn't climb a ton. You know, I was just, you know, you finally find that you fall out of the romance of it. You still love it, but that romance period, you know.... and, and that timeframe was one of the big gym booms going, everything's going, right? And then I go back and visit Joe's, and you can see it plain as day. It's like, the starting holds are three feet higher off the ground from erosion. That trees dead, that trees dead, that trees dead. There was a bush there, there was this there, and you're just kind of like, "Whoa." It changed so quickly to where it was like, well, who's gonna do something? Like who's gonna say something, or who's...? And I just stood there and I was like, "Well, why does that have to be someone? I can do it." Like I'm standing here. Why don't I do it? Why don't I help and make this sustainable / everyone else can kind of understand it, right?

Kris Hampton 40:13

Yeah, well, we're, we're sitting here now during Joe's Valley Fest. And in the last few weeks, we've watched, you know through some of your posts, some posts from climbers in Salt Lake, that two areas that are near and dear to you – Little Cottonwood Canyon and Joe's Valley– a bunch of things around the V7 level have been chipped.

Steven Jeffery 40:43

Right.

Kris Hampton 40:46

I know how you feel about it, but I want to talk about it, so...

Steven Jeffery 40:50

No, it is... So in our history of climbing, chipping/manufacturing was some sort of thing. But it was always the first ascesntionist, right? It wasn't an established thing. So that's when the beginning of manufacturing/chipping was kind of like, well, this is kind of weird, but no one had ever climbed it before. And then, if some of you remember in Fontainebleau about 15 years ago, someone very disgruntled with the Fontainebleau forest and all the climbers of Fontainebleau - the local legends, decided to take a hammer and destroy classic boulder problems. Full malicious intent, like it was all malicious "I want to get back at these people." So then it goes on further to where, those things were explainable to me in my head, I could justify being really angry and taking away something. I mean, that's how all anger, aggressions, and bad things.... someone is just angry and they need to take something because they just want to replace whatever void was created. So we get out to this point and those things, yeah. But a couple of weeks ago, in Joe's, we did a little mini trail maintenance on a boulder problem that I've climbed over 20 years ago, and the hold is enhanced with a half-inch chisel. And I sat there and stared at it. And it was a weird experience, I won't lie, it was this weird, like... first experience was like, "Huh." And then it was like, "Holy shit." And then it was like, "Mother-goddamn-fucker!" And then it was like, "Well, this is BS." And then I started grasping, going through the whole, a wave of like, "Why... what? Why?" And then I really sat there for a while just staring at it and then I tried the problem once. And then I was like, I'm not gonna climb it anymore, you know, it's, it's a different state, in a way, it was just kind of like, "This is not... what is it?" And so then it took me a while to just really start processing why. Like, what would... why would I do it? So I just really put myself in the position of like, why would I? Did I fail at something I thought I should be able to do? And it was, and it's still today, I'm still just like, "What in the world?" Like, how do I cope or deal with it? As you go through it, it's like this is not my favorite thing to think about.

Kris Hampton 43:34

Yeah, well, just to connect some dots here and clarify, because we sort of skipped right over it: The ethic used to be, many years ago, that some first ascentionists would modify things to make them doable. That has since been heavily frowned upon. So that's not even the case anymore. But especially things that have already been established, you don't change the holds.

Steven Jeffery 44:02

Right, right.

Kris Hampton 44:03

One of the things that struck me about the photos you posted, because I did the same thing, I'm like, "Why would someone do this?" Several of the holds that had been chipped, there was no chalk in the chip area at all. So it didn't look like they had chipped it and then climbed it, it looked like they had just chipped it and moved on.

Steven Jeffery 44:26

Right. So as time goes on, we find out more and more and more, you know, you start actually narrowing down who, who's doing it through that kind of stuff. So that's what was puzzling about it. But the way it worked out here in Joe's, was the holds were chipped, they're enhanced to be climbed. And then the person tried to cover it up a little bit and so they just shoved a bunch of dirt back in there and, and then the idea is well, someone will come along and brush it and maybe it'll get bigger, right? Because sandstone, it's soft, right? But the way the sandstone works in Joe's Valley is you break that first varnish layer off? Chalk doesn't actually stick to that varnish layer underneath, the chalk won't stick to it for a while until all of our over-humaned traffic juices get all over that hold. And it gets caked back up with that. So that's why it looks, it looks like that in our, in these photos. Because when you break off that layer, it's as fresh as stone gets. And so there, it's plain as day. And so the person was like, "Oh, well, God, that scar looks really bad." Because if you take off that varnish layer. So "We'll all hurry and climb it here, put up my send video," or whatever their idea is, "and then I'll just pack a little dirt in there and take off." So that's why it's taking time to actually figure out all the climbs that have been enhanced around here, because we haven't gone and climbed them because climbing season starts this weekend.

Kris Hampton 45:54

Yeah. I just read an article that sort of put the blame on indoor climbing. And I'm a little, you know in some ways, I agree with that sentiment. And in some ways, I'm really skeptical of that sentiment. What are your thoughts on it, being someone who's entrenched in the indoor world, the way you are? And you and I are both people who have helped to increase the popularity of climbing. So do you feel like there's any... like we hold some of the fault as well?

Steven Jeffery 46:34

Oh, no, yeah. It's that whole... we all want to put blame on something that we don't understand. That's our first human reaction is: I don't understand this. Makes me feel dumb. Figure out who to blame it on to get this reaction out. Make me feel good quick. Let's make myself feel good quick. And that's, that's easy for us to all fall into. So it's easy to be like, "Blame the climbing gym." Okay, blame the climbing gym. Or, "Oh, blame this, blame that, blame social media because everyone has to portray themselves as something," right? Blame... it's everything, it's everyone, it's all of them. You can't just pinpoint one. That's the stupidest. You might as well just try the same beta on the move 5,000 times the same way. As climbers, we change it and we break down what it is. So that's what I, kind of how I did it myself, because yeah, in the climbing gym industry, I see people brand new walk into the gym, and two years later, they're my climbing partner climbing the same projects I am. And it's like, "God, it took me 30 years to get here and you're so, you're the little twerp standing right next to me climbing something that I'm really having a hard time with," you know? And that fast turnaround of a climber from the gym is something easy to blame in a way. But then you go back to me and you, as these mentors and creators, helping. Well, what have we done with this to help educate people? What have I done? You have your podcasts and people can listen. And me? What have I done? I haven't done anything. I'm in Castle Dale hiding. I'm not out saying or doing anything. So I, there's, I can't blame someone. I can't, you know, I can't. I should be blaming myself, too, right? Because it's like, how to pinpoint it. But I, I'm okay personally, saying the climbing industry has a huge – indoor climbing industry – has a huge problem with it. I am totally fine with you know, calling that industry out. When we go into our gyms, go into your local gym, and when you go in there, walk around and look. Look if there's any sort of education, simple flyer, just to say, "Hey, just so you know, our climbing gym is catering to you for customer experience." Outside it don't give a shit what you think. V5 is V5, you know. This climbing area's grades are like this. Other climbing areas' grades are like this. Grades are to that area. The idea of what's dangerous? A high-ball in Bishop is a high high-ball in Joe's Valley, right?

Kris Hampton 49:20

It's, yeah, it's a route everywhere else.

Steven Jeffery 49:22

Right. So we learn as rock climbers, these places have that, right? Gyms don't. Gyms are, you know, they have pretty... they don't have regulations quite yet on how high their walls can be or, but they'll kind of follow this guideline of providing a good customer service. They're not there to scare the crap out of you. That's why there's 10 million quick draws on your wall, top ropes hanging, and padding that no human could carry by themselves to a boulder. So it's this customer experience they're creating for you and not explaining that when you go outside. So when these new climbers get really really strong, really really fast, and send your project next to you and become your friend, don't have that, they go out on their own, and they go for it. And they're really, really strong. And they can get into danger really, really fast. And they can be quick to be like, "Well, I'm really really strong. This boulder problem should be easier." And so that factor could come into play. I can see how it can come into play really, really quick.

Kris Hampton 50:29

Yeah, you can get, you can catch a beat down way faster outside than you can in the gym.

Steven Jeffery 50:34

Oh, yeah. You want a good humbling,

Kris Hampton 50:37

Your ego can get crushed.

Steven Jeffery 50:38

You want a good humbling, go climb in an area in the worst heat conditions imaginable. And then you'll just be like, "Yeah, I get it." But us as climbers, the old-school, we understand that because we've gone through it, because that's where we started, and that's where it was. And so that, you can blame that gym industry. And then I, I mean, I have social media. I have an Instagram, but I only allow 5,000 people to follow. So if you're trying to follow now, sorry, you have to wait for someone to leave. It's just a weird thing I did because it's funny to me. It's like, yeah, well, 5,000 is the limit. I don't know why I put it that. And, but that's just me being weird and I don't care. So social media, the more I deal and see with that, I see that, wow, this is an issue, in a way. We, as humans, somehow need gratification of a "like" from someone taking a crap in the woods, you know, or wherever they're staring at their phone. We need this gratification of, "Oh, someone's, someone's proud of me," or something, in a way. And so you can see how someone could get a little bit down on themselves that they can't do these things, and wanting to be like, "Let me enhance it, you know. You know, it's not that big of a deal. Everyone will be proud because they can all climb it, too." You, you can fall into that trend of like, "Why don't I just make this hold bigger?" As a route setter, it's even more dangerous, because it's like, "I know if I put a foothold there, the clientele will love this boulder problem. If I don't put that foot hold on there, I'm gonna hear about it for weeks, that I set a crappy route." So as you, as a person, you can see how easy it is to fall into these traps.

Kris Hampton 52:25

Yeah, that's, uh, you know, that's a common thing that you hear in the gym is like, "Oh, this is just a bad boulder problem." Or, "This is just awkward." I don't know that I ever heard that outside before the like gym was, the gym scene was starting to boom, because you just accepted what was there and learned to fit yourself around it in some way.

Steven Jeffery 52:51

Right, instead of just, I'll just add another red foothold right there. And then now it's fixed. You know, that's where it's that spoon-feeding of the indoor climbers that's really worrisome for the outdoors.

Kris Hampton 53:04

Yeah, we talk a lot on here about the things that climbers can do individually to make sure that that spoon-feeding doesn't impact them negatively when they go outside. But there are other things we could do. You know, Lana and I have talked about creating some sort of ethics courses that get sent to everyone who also buys our like beginner programs to help them learn what going outside means. Things from you know, not chipping, all the way to how to get in line for a route, you know?

Steven Jeffery 53:44

How does a queue work?

Kris Hampton 53:45

Yeah, exactly. Where to unpack your stuff, you know? Things like that.

Steven Jeffery 53:51

It's, it's getting there. And the problem why it's slow is information. You know, our current state of the world is we thought if we had all the information we'd be – everything would be solved. We'd be smart. And now we carry these damn devices in our pockets that just make everyone think they're a genius. And it's like, okay, genius, you know, if you have so much information in there, why can't this work? And it's a disinformation age. We're all seeing this, as we look in our phone, and I just watched someone climb this really hard boulder problem. "Oh, my God, this is amazing." But that was the 900th attempt. That was, oh, or, "Wow, how did this boulder problem come about?" Well, a lot of hard work in building a trail gaining access. None of that shown. We're not getting enough information that's correct. And so in this disinformation age with that, that's our problem. It's like, oh, well, okay. This is, I learned just enough to think I'm smart. And that's the dangerous human, right? And so these climbers are going out there like, "Well, he kind of knows enough," or "He or she's, she's been here before," but kind of. And then we're, we're comp-, we're compounding this disinformation more and more and more and it's growing and growing and growing, instead of: this is actually the ethic. This is how you get in queue for a boulder problem, you know. Because surfers will tell you real fast, they'll just punch you in the face, right? Surfers aren't gonna wait. Next thing you know, you're punched in the face and you're drowning. And you're like, "I guess I was out of the queue." climbers are a lot more friendly about it, which is cool.

Kris Hampton 55:35

Well, one of our like, historically, one of our best sources of, especially local information, has been guidebooks. You know, you're going to an area, you buy the guidebook, you learn what the local ethics are, you learn your way around where the private property is versus the public property, what you can and can't do sort of. And I think now with the like proliferation of Mountain Project and online information about here's where this boulder is, go try it. I think some of that is getting lost. And you, you just released your Joe's guidebook, which is a long time in the making, on the KAYA app.

Steven Jeffery 56:23

Right.

Kris Hampton 56:26

With the chipping that just happened, how are you feeling about having that guidebook out there on an app? Is it a good thing? Is it a bad thing?

Steven Jeffery 56:36

Right. So people that know me know I just say whatever the hell I want, and that's fine, and I'm totally fine with that. And I'm fine with myself and how I feel about things. When I had been working with KAYA for a while, with an old friend Dave Gurman, you know, it was, "Yeah, let's make this guidebook." But the second I found that chipping, the first reaction was fuck everyone. Why the fuck would I share this? Why would I care where all this stuff is? Why would I give someone the golden ticket to destroy everything? And the honest opinion of why I didn't release my book, in the beginning, was Joe's Valley was in the transition of local and climber. And my thought was, why would I put a book in the Food Ranch, and the first thing we talk about is the fragileness of amazing classics from rain, and have a local read it and go, "Well, I know how to get rid of rock climbers," take a hammer, and go smash every hold off. So it exactly happened, what I didn't want. I was, I was, it was like, "Holy shit, did I just manifest this whole nightmare for myself by not releasing it 15, 10 years ago?" Because my fear was a local, with a treasure map of gold to get rid of us. You know, now the treasure map of gold, it's like, oh, well, I don't have to worry about a local, you know, I'm about to worry about someone that's ego can't handle the grade and needs to enhance it. So it was, it's painful in some ways, right? But I see it – doing the guidebook with the Kaya app – I teamed up with the app because, for one... I'm not gonna say me and you are old, but...

Kris Hampton 58:24

Well, but we are.

Steven Jeffery 58:25

We're older.

Kris Hampton 58:26

We're relics, or at least approaching relics.

Steven Jeffery 58:29

Staring at our phone is kind of alien to us. It's a little bit weird.

Kris Hampton 58:33

I'm getting better at it.

Steven Jeffery 58:34

It gives me a headache. It's like, why am I looking at this weird device that just pisses me off all the time? And anytime something comes in on it, I'm angry. You know, it's like, oh, why would I want to look at this more, you know? It was kind of this, "Well, what do I do?" but the future of everything is, as we think about it, you know, it's helpful. We're not cutting down a bunch of trees to make a book, in some way. There's good aspects to it. And then there's the old man headache aspect to it when I stare at it, right? But these, I chose to do the app because I don't want... it's easy for us to crowdsource things, it's easy for us as humans to geotag things. It's easy. Anyone could put a video up anywhere of anything. And so I chose to do it this way because I set it up that the authors of these apps on KAYA, they control and own their guidebooks still. They're not just some off, blind admin that's, "Oh, I think it does this, I kind of stole the information from this site and I asked my buddy over here and she told me this about this boulder problem." You know, it, yeah, I didn't want this half-baked crowdsourced things. I wanted it to be authentic to where it's the guidebook author's voice. They can explain the boulder problem how they wish, they can put way better history of all the climbing in there. And when these apps can keep growing, you're, you're at unlimited space, it's the cloud of the internet, whoever knows how far that's gonna keep going. And you can just keep shoving info in there. And sure, someone probably won't read the five page novel of why it's called "Trent's Mom", but someone might and think it's the most hilarious thing on the planet. And so you can do that in your book, and you're not taking up pages and paper. And it's instant. I can, we can modify anything. So if something's changed, access has changed somewhere, you can just be like, "Yo, hey! Not just new gym climber, but hey, everyone!" you know. "I've been climbing for 20 years, why can't I come here anymore?" That guy, he's going to do that. "I've been climbing on this cliff for 30 years. No one could tell me I can't." It's like, "Well, technically, it became a nesting area for birds. And it's actually really bad if you climb here." And then that person just goes for it and next thing you know, your cliff's closed. Because the guide book didn't say that, because it's out of print. And so all that is why I really pushed to do that. I'll still do a print version that everyone can have and write in and all that stuff, but I really pushed because it's gonna happen without us. So all us guidebook authors and anyone out there, you're gonna get left in the dust. Because this will take over and, but so why not help it and grow in a way together? Versus just what one rando thinks of a boulder problem and puts it on Mountain Project.

Kris Hampton 1:01:32

Yeah, like, you know, I think that sort of evolution is a survival technique, you know, for us relics. But it's also, you know, I think guidebooks are a survival mechanism for climbing, too. A lot of the old-school idea is that if you build it, they will come, you know. You put the guidebook out, you're inviting all these people. But now, it's so easy to find that information online, they're gonna come anyway, right? And they're not going to know, you know, especially in a area like Joe's Valley where we need to keep this relationship with the locals in a good place, they're not going to know anything about the surrounding area, they're not going to know where to park when they're on that, that narrow, narrow canyon road, you know, they're not going to know which trails to take in. Joe's is a confusing ass place, you know. So it's very easy, even with a guidebook, to get lost. So without one, and just knowing, "Oh, there's a boulder up there, somewhere?"

Steven Jeffery 1:02:35

"Here are the GPS coordinates. Walk straight." Okay?

Kris Hampton 1:02:39

Exactly. So I personally think guidebooks do a good service. And having them evolve is a natural step.

Steven Jeffery 1:02:49

Yeah. And we have to, you know? It's just like climbing, you know, we have to evolve to try to climb harder. These people climbing these giant mountains, speed mountaineering. You know, they're evolving in these crazy ways. And everyone needs to understand you have to evolve yourself. Or if not, well, just, you might as well just sit on your couch and eat potato chips and watch Wheel of Fortune every day.

Kris Hampton 1:03:12

Which isn't such a bad thing.

Steven Jeffery 1:03:13

Yeah, yeah. It's good that there's some mitigation of control here and all that kind of stuff. But the guidebook things are important. And I kind of see it as, I can use this app and help provide information faster. And not be the old curmudgeon-y guy at the boulders just yelling at people expecting it to happen that way, right? My guidebook's not gonna yell at you and say, oh.... but it's information that someone can get. And then I don't have to be out there and go, "Holy shit, is this...? What is this? Does this person really think this is like normal out here? Or okay?" But I can't get pissed, because what the hell do they know? They probably, at their house, their house is probably sheer chaos. In their apartment, there's probably shit everywhere. And they're just used to that. But when they come outside, it's like, oh, you know, it's like wow. And so it helps prevent me being angry. You know, in Joe's we have a lot of good sayings about seasons around here and stuff. So I like to say, "You know it's springtime in Joe's Valley because all the license plates turn green and the tick marks start growing." And that is 100% true of Joe's Valley. If you're here in that season, if you're here in that season, Colorado just shows up and plates are green, tick marks grow. It's just...

Steven Jeffery 1:04:35

Yeah, same thing happens in Wyoming.

Steven Jeffery 1:04:37

Right. There's no way I can deny that. You know, I can't deny that. But you know what? That's just kind of like, "Oh, well, their boulders are that way." And it is. Because when I troll the internet, because I'm a troll – watch out, I troll all of you – I look and watch and I watch these videos and I'm like, "Man if you can't tell where that handhold is, you just... Obviously the boulder problem's above you." Like if you can't muscle memory these things and can't do this, you know. It's to the point where I just kind of bag on some Coloradoans, I think, who are just some randos at "Smokin' Joe", and we're up here in Joe's, and this dude has this tick mark that... I mean, I didn't, it was unexplainable, this tick mark. It looked like art to me for a minute. And I was just kind of like, oh, and I proceed to brush it away without saying anything. And I'm the bad guy all of a sudden. And I was like, "Yeah, this will be funny." I'm the bad guy. I'll just brush it away here. And I'm like, oh, yeah, I hiked the boulder problem, once. Hike it twice. As I'm doing it, I'm completely muscle memory-ing this boulder problem. And then I look at them all, and I take my hoodie, tie it around my eyes, and climb it blindfolded. And said, "You should probably do more art, you might climb it." I climbed the thing completely blind. And it's like, if this is how you have to do the boulder problem, it might be above you. Maybe work towards that better. You know, it's like, what in the hell is going on here? An old man did it blindfolded.

Kris Hampton 1:06:08

Well, Steven, it wasn't red and obvious. You have to know exactly where to go.

Steven Jeffery 1:06:12

Not glowing on a Kilter board or all those training boards. It's, yeah, but it's just... here, with with the guidebook coming, and guidebooks going, that information could be used. But then what's also important is with the guidebook, it helps give everyone else a voice, not just me being a gatekeeper. It's not me going out there and saying, "What the hell's wrong with your dog?" You know, it's, everyone has this information of, of: this is the general rules that we go with for this area. You know, because every area is different. There's invasive species of plants. People don't know this in Joe's, but the juniper tree is invasive. When I worked with the Forest Service, it's terrifying. He whips out his chainsaw, gets the smile on his face, and just starts mowing them down. And you're just like, 'No, no, no, that's providing shade" and they're just like, "It's an invasive species." None of us climbers know that. Because if you go into Tahoe and you touch the juniper, you're, you're going to jail, right? And so these guidebooks are important to create this info. So then when we're all out there and someone's new or someone's never been there, we always do that we go to someone: "Hey, have you climbed here before?" "Oh, yeah. Climbed here, this, this." "Oh, this problem is great." That's the standard exchange of climber in a lot of ways. But now that extended exchange is "Oh, but oh, by the way, it rained yesterday, maybe wait till this evening to climb," or "Oh, hey, by the way, you actually don't park in this canyon," or you don't, you know, "This is Canyon Ranch Road, there's ranchers," or you go out to cliffs, and it's like, "Well, we don't leave our draws hanging on these cliffs because..." you know. Like, that's what's important with this future of developing a guidebook, not just to give the guidebook author the voice to be this gatekeeper. Everyone that's read it, that owns it, can be the gatekeeper.

Kris Hampton 1:08:09

Yeah, and you know, you're gonna have your opinions, I'm gonna have my opinions, everyone else is, too. But really what's at stake with a lot of this information is the climbing area itself. Like we're, we're trying to make sure we retain access and a good relationship with the locals. And that's what's at stake, you know, so...

Steven Jeffery 1:08:32

Because if you really take your climbing area and break it down... so I, one thing I did to really help us in the climbing community of Joe's Valley is I'm on the Trails Build Committee with the county. I sit on a board, every month we meet, so it's all of us – Forest Service, BLM, it's OHV people, it's horse people – it's all of us, are in a room once a month talking about the future of Emery County's trails and visitation and how we, how we manage and mitigate everything. And so when you start working with those agencies, that's when you really learn, like, you're just, you're not even on their map. When you sit their map down and look at it there's white, there's green, there's... and that's that land, and that's who manages it, and that's that, that, that's that. Your climbing area can be on this. And you think you as the climber own it.

Kris Hampton 1:09:31

Yeah, you're the most important thing there.

Steven Jeffery 1:09:33

You're far, far from it. And so if you're looking to better your climbing area, because a lot of people ask me, "Well, Oh, you did all this amazing things for Joe Valley." It's like, "No, no, I didn't. A bunch of people did." It just unfortunately, the Reel Rock kind of portrays that I'm some sort of whatever of Joe's and it's like, "Well, no, no." I honestly, when I watched that Reel Rock, it kind of disturbs me a little bit in a way, because there was so many other people involved to make that happen. It wasn't just the weird hair guy that climbs out here. It's not that. It was... so it kind of bugs me a little when I've, I've only watched it twice honestly, because it kind of bugs me. Because so many people involved. So all these people always ask, "Well, how do I make? What did you do?" And it's like, well, there's simple things: you get as many people involved that has the say of that piece of property, that land, that area, and you work together to make it best. So as climbers you need to prove why you're there. Like the Bishop, they were, their coalition's going well, they're getting it, they're understanding. And you need to prove to the city of Bishop, and LA water, all those people, that you're an economic driver for Bishop. Because it's not a gas town to Mammoth anymore. There's people coming to Bishop not just to fish that river. That river there, at the Sads, though? Oh, man, it's good. If you're like a V15...

Kris Hampton 1:10:15

Steven's new love.

Steven Jeffery 1:10:59

If you're a V15 fly fisherman, that river is, the Owens through there, is world class, right? But climber see it as, it's obviously the climber cars outnumber those fishing cars, right? And so the climbing communities are understanding oh, we need to prove you're an economic driver. And your skin is in the game to protect their land, as well. It's like, "Hey, we're here to take care of your land." Because that land manager, when you meet them, they're pretty exhausted humans. They're like, "Whoa, I have 1,000's and 1,000's of acres I have to watch over. And I'm gonna have to worry about now these weird CrashPad people? It's like, holy cow. Now what?" But if the climber is there and you guys are proving your point of, "We're here to enjoy the land, too, plus, protect it," it goes really, really well.

Kris Hampton 1:11:54

Yeah, I mean, when I started climbing, I really didn't care about the environment at all, you know. I was coming from a skateboarding background. I was like, pour cement on everything, you know, skate everywhere. But because it's the, it's like the apparatus that I, you know, play on out there, you sort of have to start to care about it.

Steven Jeffery 1:12:18

Right.

Kris Hampton 1:12:19

I want to make sure we don't totally come off as like, old and crusty. I mean, we're gonna be 95%, regardless. What are you loving about climbing right now? You've been in this game for a long time. You've seen it from a lot of different perspectives. What are you loving about it?

Steven Jeffery 1:12:39

I mean, there's been moments where I've just been like, you know what, "All you people fucking go away."

Kris Hampton 1:12:45

This is not what you're loving, Steven!

Steven Jeffery 1:12:47

Right, you know what I mean? And I kind of love feeling that and saying that, you know? I kind of was like, "Yeah, fuck you," you know? Kind of like...

Kris Hampton 1:12:57

The unofficial Mayor Troll of, of Emery County.

Steven Jeffery 1:13:01

Right. But then I started realizing and you start seeing,... like, you remember the time when you and your friends climbed that boulder problem for the first time. You remember how excited we all were, and the fear, and the game, and, and you step back, and you watch people do that again and again and again, every day. You sit under this boulder problem and you're like, that's exactly how me and my friends were. We said the same things. We fell at the same point and thought we were peeing our pants. We, we... And you're watching it and this is 20 years later. And they didn't see a video of me doing it. They didn't see...

Kris Hampton 1:13:41

It's 30 years later, Steven.

Steven Jeffery 1:13:42

30 years, actually. Yeah, it's 2020, 20-something... But they're experiencing what we did 30 years ago. And there was no book written about what we did. They weren't copying anything we were doing. They were just doing what we did. And it was, that is awesome to see. That is what makes me go, "You know what? Climbing is pretty bloody rad." Because here they are experiencing the exact same thing. And it's in the same state, 30 years, it's– The foothold might be a little greasier, might be a little more chalk, the landing might be a little better or worse, but it's the same experience they're having as that new climber. And that's what really makes me happy about going out there and climbing with everyone. Because, no offense to all you strong climbers, but I could care less that you climbed the hard problem.

Kris Hampton 1:14:12

Same.

Steven Jeffery 1:14:13

You should be able to climb the hard problem because that's all you guys are doing. It's like, if you didn't climb the hard problem, I would actually – now you know why I make fun of you – because I'm like, "Here, jackasses. This is actually easier than the problem I heard you did last week and you can't do it." But when you're in a group of people and you walk up to that boulder problem, you will notice, there's always someone sitting back there that won't even try the thing. And that person's the person I'm like, "You should try it." And when they do one move, the excitement they get, in the battle of just the one move? And then maybe 30 minutes later, next thing you know, they do it. That's what I love about climbing now, that's what's cool to me because, honestly, all you strong kids are posers. I think you're all posers. You should be doing those things first try, because that's all that matters.

Kris Hampton 1:15:27

That's the soundbite that's going on Instagram. "I think you're all posers."

Steven Jeffery 1:15:30

I think you're all posers. Because you should have done it first try. Because, I mean, it's only V12, you climb V15. First try would be more impressive. Yeah, yeah, you can try it 50 times and do it. That's great. But he did it on like 500th try. You know, but this person back here, trying this V4, the hardest grade of their time, and freaking battling for it, and 100% doubt they can do this thing, and they do it? That's amazing. That's what climbing is.

Kris Hampton 1:16:01

I definitely resonate with the idea that anytime I say something positive, I also have to follow it with, you know,

Steven Jeffery 1:16:10

A little beatdown.

Kris Hampton 1:16:10

...talking shit to somebody. But um, you know, I'm glad that climbing is still giving something to you. You're still getting something out of it. Because you put a lot into it. You know, from, from just photos of you and videos of you getting people psyched to try their absolute hardest. You know, when I'm, as a Red River climber, I'm not good, naturally, at just trying really hard right off the ground. But I can think about a Steven Jeffery's video or photo and try to channel that same aggression into what I'm doing. From those days, to route setting, to developing boulders outside, to helping create this really unique relationship with Joe's Valley climbers and Joe's Valley area locals – you've given a lot to the sport. So I'm glad it's still giving things to you.

Steven Jeffery 1:17:09

And it will, because I'll always find what it does. And right now, what's amazing... I don't show it, because I'm not soft. If anyone thinks I'm soft, that's BS. I'm not soft, okay? But I don't want to show it...

Kris Hampton 1:17:28

You did join a trash cleanup here in Orangeville, just saying.

Steven Jeffery 1:17:31

I'm not soft. Sometimes it appears that way. But when people come up to me and they thank me for all the Joe's stuff and trails and all that stuff – I may be like, "Yeah, whatever, kid," but deep down inside, I'm really proud of it. And I'm proud that these people are enjoying something that I luckily have the time to do for us all.

Kris Hampton 1:17:54

It makes your little heart grow two sizes too big?

Steven Jeffery 1:17:58

Right, right. Yeah, that stuff is, it's, it makes you feel like it's worth it. And I like to deep down inside think that those people that really come up to me and say that and truly heartfelt mean it – they mean that they would do it, too. They just don't, unfortunately, have the time like I do.

Kris Hampton 1:18:16

And sometimes they will. Someday they will.

Steven Jeffery 1:18:19

Right.

Kris Hampton 1:18:19

And there's lots of ways to contribute. And I think you've shown that through the years, too.

Steven Jeffery 1:18:23

Yeah. Simply, they'll roll a little rock out of the trail when they're walking by and that's, that's, that's a contribute to helping. Yeah, I mean, they're not building miles of trail, but there's little bits. And that now is, honestly, I'd rather build trails and fix landings then go climbing right now anyway, because it's kind of, it has this feeling of accomplishment, just like summiting a route, a mountain, a boulder problem. It's this accomplishment. And it's a shareable one. Yeah, it's not a selfish "Oh, I climbed V15."

Steven Jeffery 1:18:27

And it's back to that same creation you were doing, setting boulders for people for the first time, you know.

Steven Jeffery 1:19:05

I never, in my route setting days back then, I never set a route for me. I never set a boulder problem for me. It was always for the customer base. It was for my friends and they'd come in, you could see they were having a rough day at work. And here they are climbing on my route and you can see their day change. That's why I did it. It was not to be "I'm the cool guy." I could care less. Because as I stated, all you posers, I don't want to be you. I don't want to be the poser guy, even though yeah, yeah, you're doing legendary stuff or whatever. You're climbing something hard. You're still a poser, you know?

Kris Hampton 1:19:43

Well, dude, I appreciate you sitting down. I know you get a lot of requests to do this and are reticent to talk sometimes, so...

Steven Jeffery 1:19:51

No worries, man.

Kris Hampton 1:19:52

I appreciate it.

Steven Jeffery 1:19:53

No, it's good. It's nice to be able to be understood.

Kris Hampton 1:20:01