Love It or Leave It

Do you really want this or do you just like the idea of it?

When we really and truly want something, we find a way to make it happen. You see so many climbers reach incredible levels of strength and skill using all different methods. One thing that they have in common is the desire to improve.

When we struggle to make something happen, the first thing we normally blame is ourselves for not having enough discipline. If only we could knuckle down and focus then we’d be successful. What if that’s not the problem? What if you’re spending time chasing something you don’t really want?

Photo by Rowland Chen

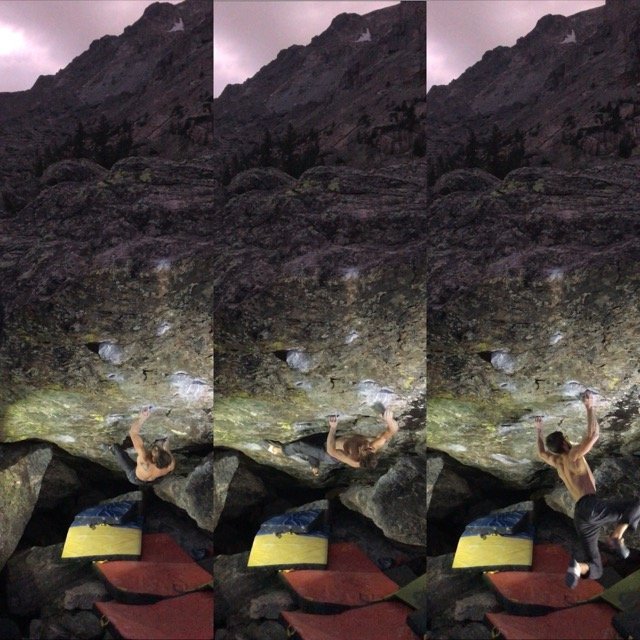

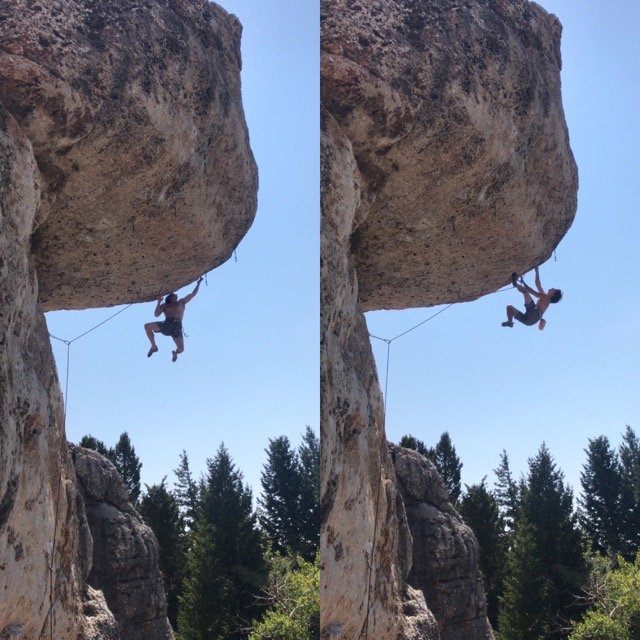

Many climbers will have breakthrough moments later in their careers when they decide to shift their focus. Maybe they kept chasing sport climbing for years longer than it held their interest, and a move to bouldering renewed that initial flame of excitement that climbing gave them. For some people, they find that they would rather climb inside an extra day or two a week instead of outside. They always felt like they were rock climbers so they had to climb on rock as much as possible. Now though, they value having more time in their life for other things and those shorter gym sessions allow them to have that balance. By leaning into that feeling, they now bring more energy and dedication to those gym sessions than they did to trying to squeeze in a day at the crag around an already busy schedule. That extra motivation in the gym helps them to push themselves harder, and now when they do go outside to climb they are sending harder than before.

If you want to find success, it’s important that you make sure that the thing you are chasing is something you actually care about. If your starting point is genuine then success will come more naturally.

Long-time friends Nate and Ravioli Biceps discuss lessons they’ve pulled from video gaming that can help inform our climbing.

I never thought I’d be recommending this, but some of y’all should be putting less effort into becoming technically better climbers.

Do you really have terrible willpower? Or are you surrounded by distractions and obstacles?

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

Discussion around grades can be so polarizing that many of us avoid the topic.

Climbing starts off as this self-feeding cycle that has you wishing you could climb seven days a week. What happens when this cycle stops bringing improvement though?

Use strength to leverage every other aspect of your climbing, not replace them.

If everything you do is a finger workout, then when do your hands get a chance to recover?

There is a common theme between a grilled cheese sandwich and good training advice.

The more accurately we define our problems, the more approachable it will feel to find solutions.

Maybe the most understated way of getting better is to build fallback successes into your plan.

How much time should climbers spend becoming more well rounded vs. improving their strengths?

As cool as assessments and standards are, they can easily leave people settling for “good enough” when they have the potential to do much more.

Being able to quickly recognize familiar sequences is a crucial ingredient to harder climbing.

It’s far more comfortable for us to blame ignorance for our lack of progress than it is to blame our own efforts.

Once you learn the power of good tactics it can be hard to step away from them.

Of all the people that I spoke with this year who were stuck in plateaus, many of them had the same thing in common: they climbed and trained alone.

The belief that you are getting better at climbing is one of the most important ingredients in actually getting better at climbing.

How many times have you gone up a route and felt overwhelmed, only to look back and realize that it’s not as intimidating as it initially seemed?

Most of us go into a training plan or an outdoor season with an expectation, but expecting results can make us brittle when problems arise.

Whenever there is a training article online or some tidbit of knowledge on social media, it’s important that you consider the context.

At a certain stage in climbing, the hand and foot beta you use stops being the deciding factor in whether or not you are successful.

The intermediate climber’s problem with perception starts to arise when they can’t recall all of the solutions they have attempted during the problem solving process.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.