The Worst Reason to Not Improve

What is the worst reason you have for not getting better at climbing? We all have these things. We know it’s what we should be doing, but we can’t be bothered to follow through on them. These opportunities for growth are so easy and simple that they feel embarrassing to say out loud. A bar set so low we trip over it.

How many things are you avoiding, not because they are hard, but because they aren’t exciting? Is that really a good reason to not be getting better — because it’s not the most fun thing you could be doing with your time?

When I work with climbers to help them find ways to improve, I’ll often bring up the hard things that they are avoiding.

When I bring up one of these — like not trying hard enough projects or needing to spend more time working on their onsighting — they pause, accept this with full seriousness, agree that this is something they need to do, and then resolve themselves to working on it from this point forward.

Don’t let bad tactics be the reason you have a poor session. Also, consider moving out of states where 50+ days of 100°F in a row is normal.

On the other hand, when I bring up one of these embarrassing things that’s easy to resolve, but up to this point the climber just couldn’t be bothered to do anything about, they will look at me with a bit of a guilty grin, shrug, and say, “I’ll see what I can do.” Nothing is ever done about this.

Why is it that we can look at something truly challenging or intimidating and steel ourselves to go for it, but when an easy win isn’t fun we throw up our hands as if to ask, “What can be done?”

Some of the common occurrences of this include:

Not stopping to thoroughly read boulder problems or routes before you pull onto the wall for the first time. You miss holds and sequences, and end up having to give extra go’s to correct what an extra 15 seconds of observation would have prevented.

Not doing any mobility work even though you know it’s a weakness. You have the time for it, but it’s not as fun as other things.

Avoiding slopers because you enjoy crimp climbing more.

Skipping the warm up because you don’t feel like doing it, even though you know you climb better when you warm up well.

Getting less sleep because you spend an hour every night doom-scrolling through social media.

Rock climbing is a lot of fun. It’s one of the reasons so many of us get hooked by it the first time we try. With how much fun we have every day that we climb, how hard is it to add in a few menial tasks that will ensure we continue to improve? What easy wins are you missing out on?

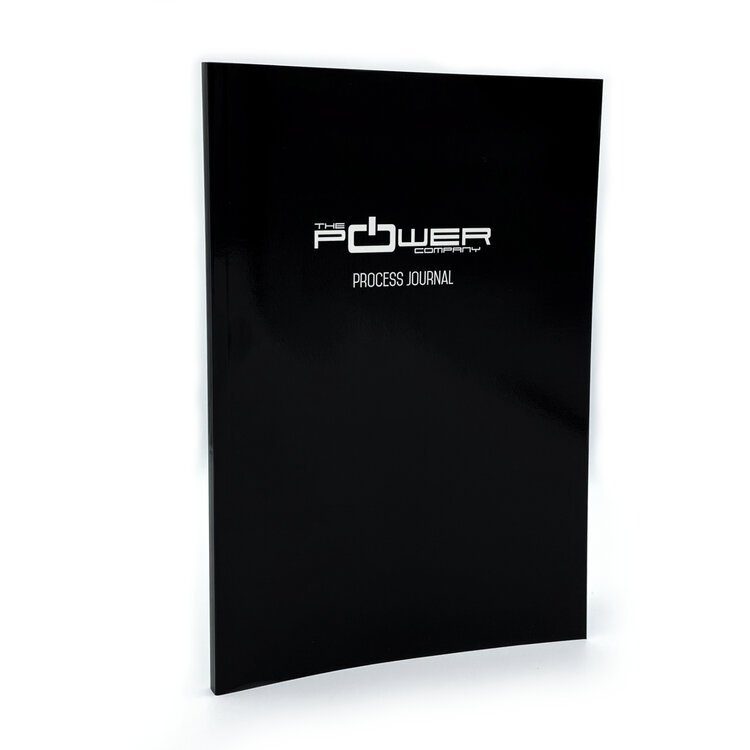

If you’re looking for an easy way to find these low-hanging fruits in your climbing practice, try out our Process Journal. It was designed to help you bring more intention to your training and practice, as well as spot patterns that are both helping and hurting your climbing.

Designed for both indoors and outdoors, climbing or training, the Process Journal is a three month mindfulness/awareness journal. It was specifically created by our coaches as the simplest way to ensure that your climbing practice is producing the results that you're looking for.

Softcover 6"x9".

Switching back and forth between sport climbing and bouldering can be difficult…

Alex Megos once said that conditions don’t matter, but we all know that’s not true… or is it?

There’s one often overlooked thing that has the power to positively – or negatively – affect every single day of climbing for the rest of your life.

There is a point at which continuing a tactical approach can slow your climbing gains.

Toe-hooking can seem more like sorcery than other techniques, but you’re probably just going about it the wrong way.

Implementing this one simple thing can result in big performance gains in your climbing, no matter what level you’re at.

Despite being constantly present and often the reason we fail, Rhythm is the most underrated of the Atomic Elements of Climbing Movement.

Long-time friends Nate and Ravioli Biceps discuss lessons they’ve pulled from video gaming that can help inform our climbing.

There’s A LOT of great information out there on how to climb harder. But it’s tough to sort through…

Short climbers are good at getting scrunchy, and tall climbers are good at climbing extended, right? Wrong.

One of the most common places things start to fall apart is at the very beginning of the move.

We know spending time on a finishing link is smart tactics for hard climbs. So why not apply the same concept to individual moves?

Learning when and how to compensate for a weakness is a skill. And skills need to be practiced.

Lowball boulders, while not as proud, can still teach us new movement, new ways to utilize tension, and force us into finding new techniques.

I never thought I’d be recommending this, but some of y’all should be putting less effort into becoming technically better climbers.

Training principles are important, but when they creep into performance, your climbing will suffer. Nearly every time.

We have become collectors of dots. But there’s one major thing that happens when we connect dots that is entirely lost in mass dot collection: critical thinking.

Do you really have terrible willpower? Or are you surrounded by distractions and obstacles?

You have a climbing trip coming up. The rock is different. The style is different. Your pre-trip time is short and the number of days you’ll be climbing, even shorter…

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

Discussion around grades can be so polarizing that many of us avoid the topic.

Climbing starts off as this self-feeding cycle that has you wishing you could climb seven days a week. What happens when this cycle stops bringing improvement though?

A better way to view grades and progression?