He SAID, She SAID.

Choose wisely... or just do some actual training...

If you aren't friends already, let me introduce you to the SAID Principle. The SAID Principle is one of the simplest, most important concepts in sports training. The acronym "SAID" stands for "Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demand."

In plain english (which I usually need to really grasp what the hell sports scientists are talking about), it means that as you provide your body with stresses, it gradually gets better at handling those specific stresses. The key word here is SPECIFIC. You've been running 5 miles a day for a year now, and your steep climbing endurance hasn't improved? Who woulda guessed? A young climber asked me just yesterday in the gym, "How do you get that kind of endurance, other than training and laps?" Well, you wish upon a star, dream a little dream, and choose the blue pill or the red pill. However, regardless of the pill you choose, neither of them will be the magic potion for endurance, or power, or technique. To get those things, you have to practice THOSE things.

"Now hold on just a second", you say. "What about hangboards, and core workouts, and campusing, and hanging out at the gym chatting with the hot girls?" You might have a point... but probably not. Fact is, most of us don't need any of those things... we just need to climb more, and be more specific about the style of climbing we're training on. If you want to climb 5.13 in Red River Gorge, then doing V9 dyno's at the gym to show off for the new girl won't help you. I promise, you just look silly. Not to say that hangboards, core workouts, and campusing are bad. They are, in fact, great specific exercises you can utilize WHEN YOU'RE READY. But we'll get to that...

If we take the SAID principle at face value, we'll be missing out on three very important, and potentially limiting, factors.

First, how much demand is enough? Too much stress could quickly and easily result in injury or overtraining, while not enough will leave the body with no reason to adapt. Luckily, we're climbers. If you're working on endurance, and you fall because you're pumped... you've given your body a reason to adapt. If you're training power, and you fall because the move is too hard... you've given your body a reason to adapt. A simple rule is to give your body just enough stress to reach failure at a prescribed point (e.g. while anaerobic endurance training you'll want to fail after 12-15 moves, but while power training you should reach failure in 1-3 moves.) If you never fail, its safe to bet that you're improvements are coming very, very slowly.

Second, exactly what demands do I need to provide? This is where it pays to have a knowledgeable coach, trainer, or partner, or just be exceptionally good at self analysis. If you can target exactly what you need to work on, be it power, endurance, or specific techniques, then you are ahead of the game. Be diligent and honest in your analysis. Did you fail on the powerful crux because of a lack of power, or because your footwork was sloppy? Or did you just psyche yourself out? It can be tough to accurately diagnose your deficiencies, but time spent doing so is time well spent

Climbing is, without a doubt, one of the most complex sports we know. It combines thousands of movement possibilities within the separate pursuits of power, endurance, and technique. Once you've reached a certain level of "mastery" it becomes more efficient to work on the specific components of climbing individually. That level of "mastery" is subjective, and it's tough to put a number on when you should stop just climbing, and start engaging in sport specific exercises. I'll do it though. 5.12c. I believe that most reasonably fit people can redpoint 12c by doing nothing more than simply learning technique, gaining good power and endurance, and focusing their "training" to be more like the type of climbing they'll be pursuing outside. Once you're around that level, some types of sport specific training will be just what you need to keep improving. The big question: Will it transfer to actual climbing?

Specific

Adaptation to

Imposed

Demand.

Specific. That's the key word. Nearly all climbing specific exercises that will successfully transfer to the rock have one thing in common... they all zero in on one small component of climbing, and practice it without the added difficulties of introducing the other 4539 processes going on in your body while climbing. The "real climbing" gains you stand to see from these exercises (campusing, hangboarding, etc...) are best realized ONLY when all the other areas of your climbing are solid. No amount of finger strength can consistently substitute for poor technique, and so on.

Basically, if you want to get better at climbing, then go climb. Alot. Try hard. Learn more. If you aren't climbing 12b/c or bouldering V5/6, then the best thing you can do for your climbing is to climb some more. And more. You get the benefit of the chance to learn so much more in one session of climbing than any 14d climber can gain in a year. If you have reached that higher level, be very picky in the ways you train. Focus on what you want to get better at, and train exactly that. Exactly. Specifically.

Tell 'em I SAID so.

Starting where you are is an important first step that is often missed.

Joy Black is a strength and climbing coach specializing in working with pregnant and postpartum climbers.

There's a fine line between reactive and proactive training. If you're constantly being corrective or reactive, you may want to rethink things.

How should we separate training and performance when they both occur in the same environment?

Co-founder of Tension Climbing, Will Anglin, talks movement skills, how climbers can continue improving, and the tools that can help.

Training principles are important, but when they creep into performance, your climbing will suffer. Nearly every time.

Looking to climb on sandstone cliffs full of high-angled crimps? Look no further than the Blue Mountains, Australia’s sport climbing mecca.

Does kneebarring hard boulders make you stronger? We're conflicted.

Looking to climb on beautiful limestone cliffs full of gently overhanging crimps? Look no further than Ten Sleep, a picturesque canyon nestled high in the Bighorns.

Giving artificially low grades to climbs increases their perceived value for our training and development. The more something is mis-graded the more we naturally want to prioritize it.

We REWIND to this classic conversation with Jonathan about when and why to change things up in your training, and one thing that training should definitely include a whole lot of: climbing.

We REWIND to this episode with British climbing legend, Stevie Haston.

Kris chats with our very own coach Nadya Suntay to remind us why it’s better to keep it simple when it comes to our training.

Looking for a summer sport climbing destination? Look no further than Wild Iris, with its high elevation, low humidity, and perfectly-pocketed limestone walls.

Our very own coach Jess West provides valuable insight as to how setters can smartly and safely train for their goals.

Maybe the most understated way of getting better is to build fallback successes into your plan.

Paul joins Nate and I to discuss the Top 6 Training Myths, of many we see, persisting in the climbing industry.

Training doesn’t have to stop just because your gym is closed.

Yves Gravelle is a legendary Canadian strongman, and pound for pound may have the strongest grip in the world.

Australian climber Anna Davey has big goals, and the dedication to get there.

I don’t have much experience with making rock climbing feel easy. What I do have experience with is transforming myself from a lover of 5.10 trad climbs to a sender of 5.13 sport climbs.

Part three from Nate: training in December and January, how I spent my time in Hueco to keep preparing myself for sport climbing, and what I’m doing from here.

Nate reviews his 2018 in regards to goals, training, climbing, numbers, injuries, and lessons.

My perception of what I was capable of, what could be possible, how hard I can push myself, the belief, the confidence, was all very much changed through a mere three weeks of training.

Sod’s Law states: “Anything that can go wrong, will always go wrong, with the worst possible outcome.” Turns out, Sod generally spends his time at the climbing gym.

When should you be growing your skill set and when should you be focused on one aspect of it?

The difficulties of a task should be such that they help the learner translate the skill to performance.

We think we know exactly what climbing looks like. We’ve zeroed in on the details. And in this case, it really isn’t those details that matter.

Nate provides more depth to the reasoning behind many common finger training methods.

Five days. Five episodes. One theme. Common sense isn't always common practice.

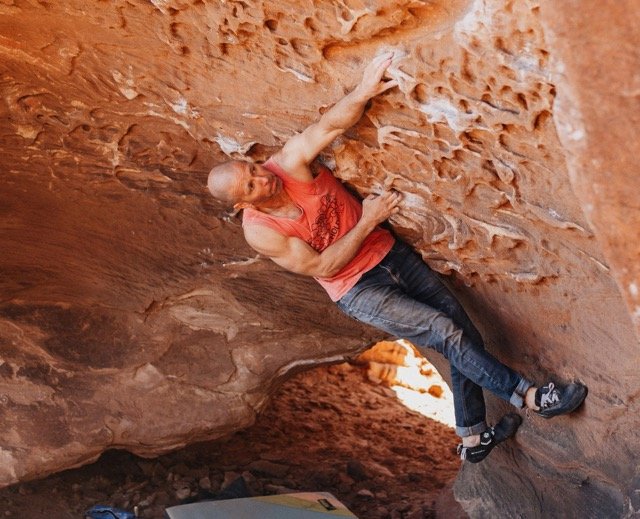

A climber since 1994, Kris was a traddie for 12 years before he discovered the gymnastic movement inherent in sport climbing and bouldering. Through dedicated training and practice, he eventually built to ascents of 5.14 and V11.

Kris started Power Company Climbing in 2006 as a place to share training info with his friends, and still specializes in working with full time "regular" folks. He's always available for coaching sessions and training workshops.

How do you know which is right for your situation?