Your Partner Might Be TOO Good

PRESENTED BY THE CLIMBING ACADEMY

While making the most recent season of Written In Stone, exploring the 1980s, I took a bit of an unplanned detour to learn about the role that women were playing in a sport that was vastly male dominated. In my initial research, women hadn’t shown up as much as they had in the ‘90s, and I wanted to understand why. This segment is from an episode titled “It Wasn’t Because They Weren’t There”:

In 1971, the relatively newly-formed Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women had 278 charter higher-education institutions where women were allowed to participate in some sports. Out of over 2800 total colleges and universities. By 1981, that number was up to 800 out of over 3200. So women in sports wasn’t exactly heavily encouraged.

Despite the passing in 1972 of Title IX – which theoretically banned gender-based discrimination in educational programs, including sports – women were not allowed to run in the Olympic marathon until 1984, and they weren’t allowed to compete in all events until 2012.

So young women finding rock climbing in the 1970s and 1980s was nothing short of a miracle. And the vast majority of recorded history ignores the contributions of women in those early years, when those women were fighting to establish themselves as athletes as much or more than they were fighting for the send of some specific climb.

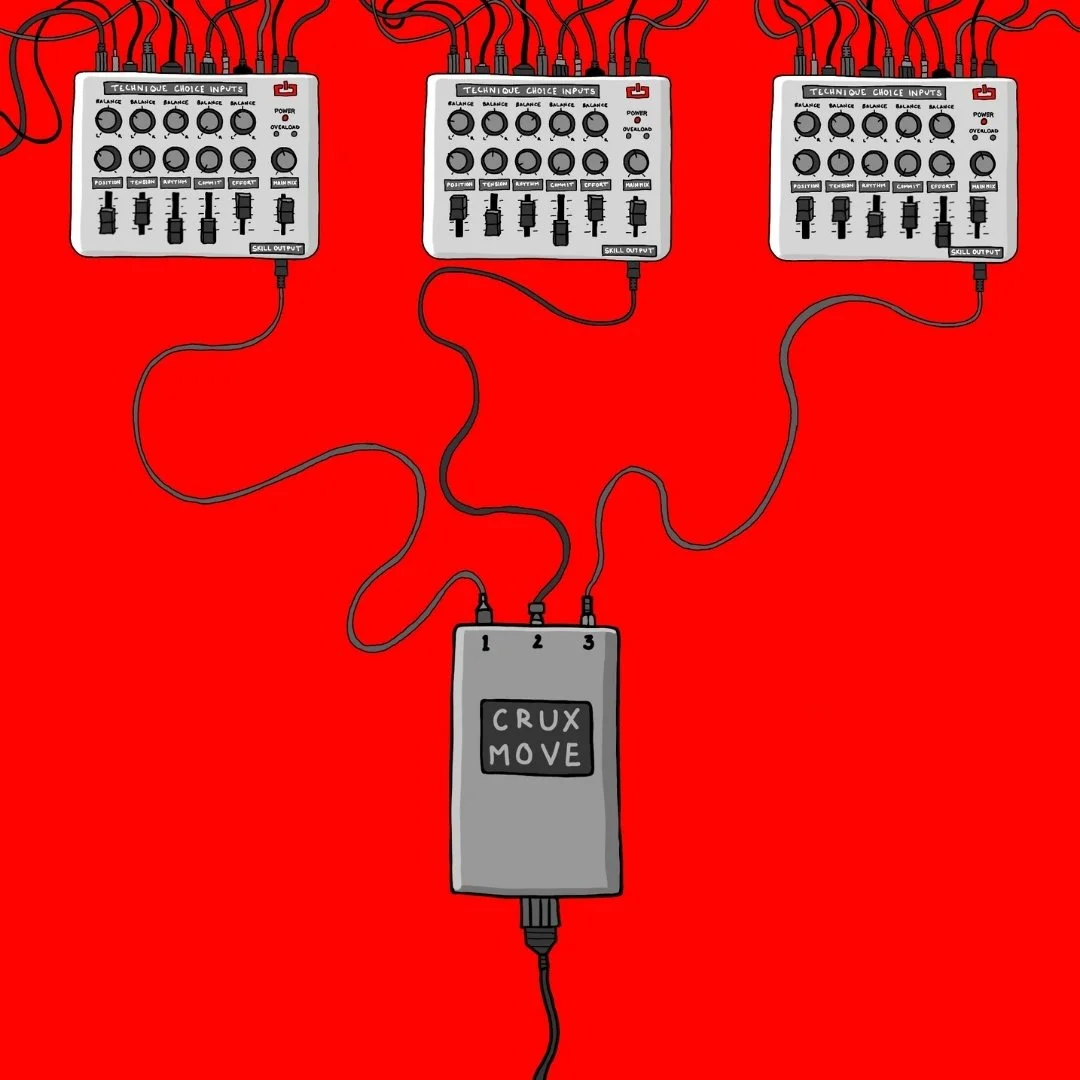

The entire eight episode exploration was enlightening, but one piece of what I learned has transitioned from my climbing history brain into my climbing improvement brain. Starting with British ace Jill Lawrence, several women echoed a similar sentiment:

When they stopped climbing with their much better male partners is when they really improved.

Once I fully transitioned this over into my improvement brain, I began connecting the dots back to a book I read many years ago called Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing. Among the stories in Top Dog is one that always stuck with me: a series of studies undertaken on incoming freshmen at the US Air Force Academy. In short, they had already discovered via data analysis that freshman learned better from other freshman and sophomores from other sophomores, but now they wanted to raise the level of the lowest performers, so they put them into squadrons alongside the highest performers. Makes sense.

But the lowest performers got worse.

They repeated the study the following year and got the same result.

However, when they looked at the middle performers, who had been moved into their own homogenous squadrons in order to make room for the experiment, researchers discovered that the middle performers improved dramatically. They were the only students who did.

The reason, I think, is that despite the Tim Ferris-ification of learning that makes us believe we need to hear from the top performers, we actually learn better from the people who are closer to our peer group. In general, there’s higher motivation and a psychological safety that isn’t present when the playing field isn’t exactly level.

I’m sure Adam Ondra and Janja Garnbret can teach us all a lot about climbing, but I fully believe your performance will be more affected by someone only a little better than you. Or maybe even not quite as good.

But it’s not as simple as just finding a partner around your level. They also have to want to give that assist. It also might help if there is some inherent friendly competition — something you’re unlikely to feel against Adam or Janja.

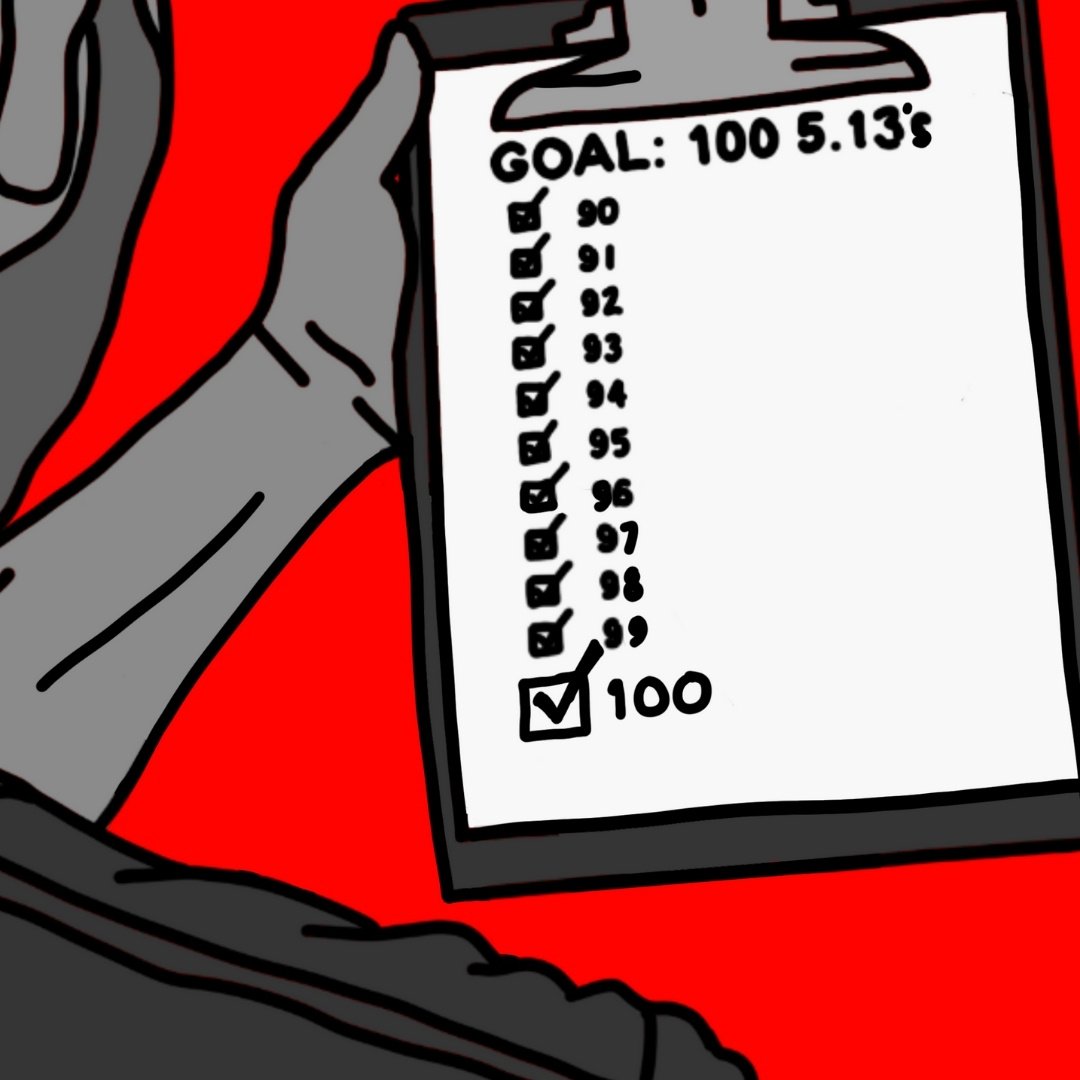

In Adapt, I wrote about Wayne Gretzky stats I had come across that I wish climbing would learn from. Essentially, when Gretzky scored goal number 802 to take the lead as the all-time goal scorer, he already led the league in points.

How?

Turns out, the NHL gives points for both goals AND assists, and Gretzky had already been the all-time assists leader for eight years.

I’ve always held that to be the best, you have to be a little selfish. But here was Wayne Gretzky — the best at scoring goals AND the best at helping other people score goals. When we look at the all-time assists leaderboard, Mark Messier and Paul Coffey, #3 and #6 on that board, were key teammates of Gretzky in his highest scoring years. Not only could Gretzky improve his performance because he had teammates willing to make the assist, but they are on that all-time list in part because Gretzky chose to take the shots he did.

They actually improved because Gretzky understood when to be selfish.

This selfless/selfish balance happens because the NHL incentivizes making the assist. It’s part of their scoring system.

Imagine if climbing had a similar system!

With these two ideas combined — that we learn more from our current peers and that getting better at giving assists can make us better performers overall — I wanted to talk with someone who worked with teenage climbers, not necessarily on a competition team, to see what they thought.

As far as I’m concerned, there’s nobody better than Kyle O’Meara for this conversation. Kyle has worked as a competitive team coach, but more importantly, he’s also coached at The Climbing Academy, an alternative high school that spends semesters in climbing destinations around the world. As part of their Core Values, they say they’ve “adopted a team approach” to “a sport that is perceived as an individual endeavor.” They claim that “being part of a team that is centered around a dynamic and challenging sport helps students understand the value of working together and of making sacrifices that serve the community as a whole.”

I wanted to know if they actually tried to teach this in their curriculum and how it affected the students’ climbing performance as well as their overall experience with climbing.

SPONSORED BY THE CLIMBING ACADEMY

When I approached The Climbing Academy about making a video focused on how partnership could affect performance, they not only agreed to contact students and alumni for me, but decided to sponsor the video and this issue of The Current. They believe in their mission, and after hearing stories from several students as well as talking with Kyle about his time coaching there, so do I. Mentorship is alive and well.

Also in their Core Values, they say that one of their main goals is to “enrich young lives by providing learning experiences that help students develop in character, as well as academically and athletically.”

I think that’s what we all want from climbing.

Climbing Academy students sharing beta in Rocklands.

The 30-minute video that resulted from talking with Kyle, digging into the research, going down the Wayne Gretzky rabbit hole (he was recently passed on the all-time goals list — more about that in the video) and hearing the story of Sylvie, a Climbing Academy alum who was trying her hardest route ever, is up on the YouTube right now. In it, I cover three main surprising takeaways:

We can potentially learn more from other climbers around our own ability level, rather than always looking to the pros.

Friendly competition can be a valuable tool to promote higher effort, faster motor learning, and better decision making.

Being a little selfish is actually being a GOOD partner.

I always enjoy talking with other good coaches who understand that climbing goes much deeper than finger strength, and Sylvie was particularly open when talking about feeling competitive and the realization she had while talking with her partner, Lena.

Maybe most fascinating for me is that while recording the interviews and going over submissions, there was an overlapping story. I almost didn’t connect the dots — that happened during the making of the video. For that though, you’ll have to watch.

I’ll see you again in a month or so.

– Kris

Related Things to Stay Current:

My last couple of months have been focused on tiling our shower and finishing the first Written in Stone book. Looking at some of the most important ascents of the 1990s and what we can learn from climbing in that decade, it’s available for pre-order for the WIS Patrons now. It’s free to join.

The full conversation with Kyle O’Meara that I used to make this video will go out to Power Company Patrons soon. Nate and I also recently spent several hours discussing which training interventions are theory, tradition, or tried and true. Some might surprise you.

If you haven’t yet, check out the FREE Try Harder Toolkit.

Don’t forget! If you aren’t on the email list for THE CURRENT, you won’t get the email next month. Make sure you’re subscribed HERE.